Listen to this article

Listen to this article

Loading

Play

Pause

Options

0:00

-:--

1x

Playback Speed- 0.5

- 0.6

- 0.7

- 0.8

- 0.9

- 1

- 1.1

- 1.2

- 1.3

- 1.5

- 2

Audio Language

- English

- French

- German

- Italian

- Spanish

Open text

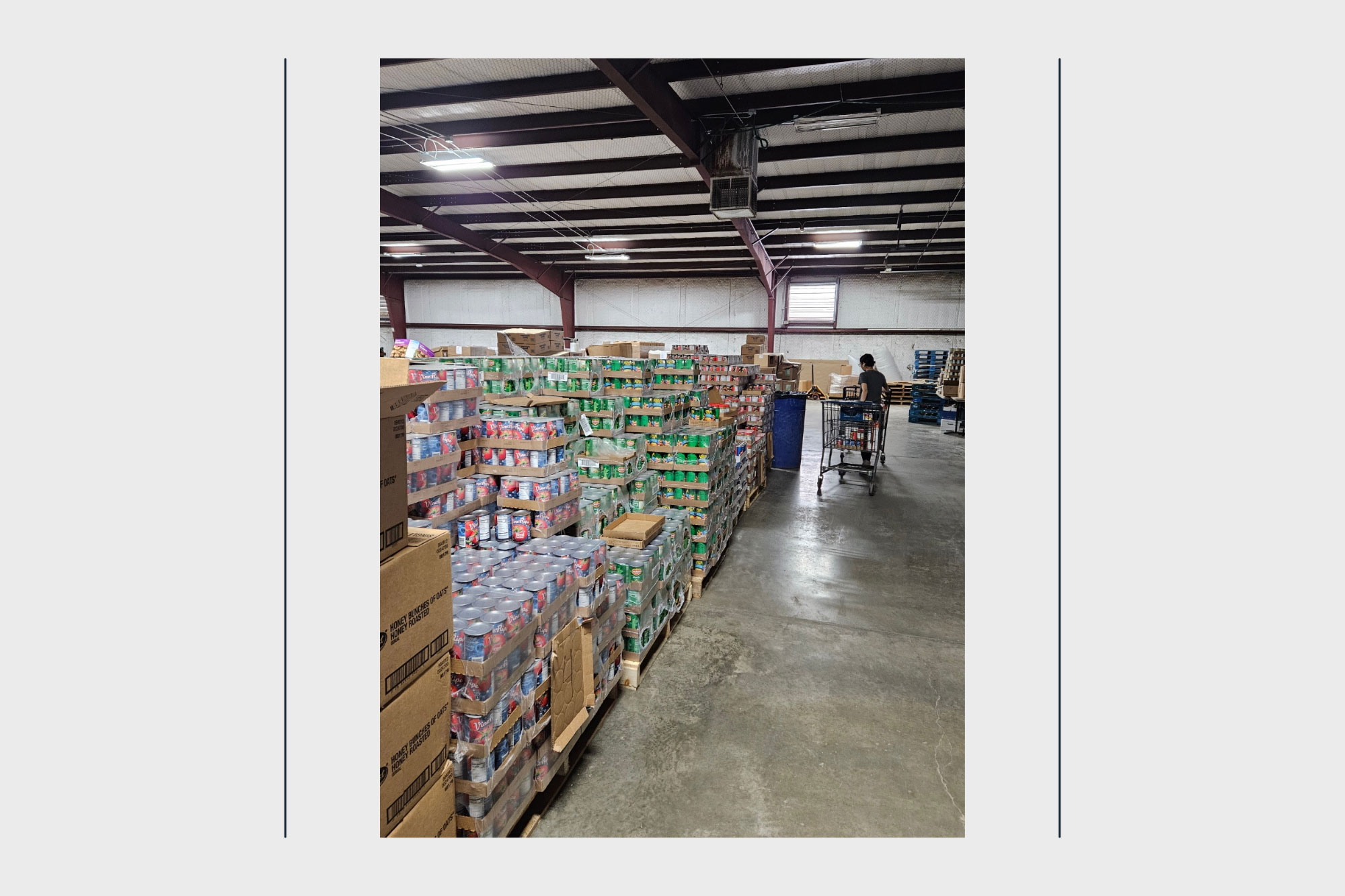

unscathed. aaron varela maldonado after dui, teen’s legal residency hinges on sobriety. drunk and high on cocaine, aaron varela maldonado climbed into the driver’s seat of his car with a friend riding shotgun in late january 2015. with neither passenger buckled in, maldonado lost control of the vehicle and missed a sharp turn, crashing into a tree in vail, colo. though neither wore a seatbelt, they emerged relatively unscathed. but even the crash, spending the night in jail, and being charged with a dui wasn’t enough to make him stop using drugs. it all started when maldonado first tried drugs at 15 years old. it wasn’t a sip of beer or a puff on a joint. it was crack cocaine, given to him by his uncle, which sparked a seven-year drug and alcohol habit. by age 17, maldonado’s mother and stepfather were finding weed pipes and liquor bottles in his drawers. he’d often come home with his face bloodied from fights. “they knew i was out of control,” he said. “they kicked me out a few times but they’d always take me back. and i never stopped using.”. his mom and stepfather finally asked him, “why are you always drunk?”. “i told them, ‘i can’t stop,’” he said. maldonado learned of the adult rehabilitation center (arc) in denver, a facility run by the salvation army that provides low-cost and free treatment to those in need. everyone is welcome, so long as they are willing to participate in the biblically based program and work to fund their stay. though initially reluctant, maldonado applied and was accepted. april 17, 2015, marked his first day in the program. “i never tried to quit an addiction before,” he said. “i heard all of these people talking about what it was like when they were using. i started looking for a sponsor.”. and then, just two weeks in, he got terrible news. his cousin had died during an epileptic seizure. at first, he just wanted to leave, he said. but instead the program supervisors gave him a pass to go to the funeral. “at that moment, everyone found out and started supporting me,” he said. “people who didn’t know me came up and gave me a hug. right there, my second week, i started feeling like i didn’t need a substance to make me feel better. the support was incredible.”. when he returned from the funeral, he took a breathalyzer test and a urinalysis, both of which he passed. it was a milestone. “the program is six months long and we find that the first 30 days are the most critical in the success of a beneficiary,” said lt. allison struck, who runs the arc along with her husband. soon, the strict routine felt like home, maldonado said. the days started with breakfast at 5:30 a.m., followed by morning devotions before heading to work at the arc warehouse where he’d help sort donations for four arc thrift stores. after work, maldonado would sneak a shower in before dinner, which was followed by classes like rehab issues, anger management and relapse prevention. after class, he attended bible study and an alcohol anonymous (aa) meeting. the meetings ended at 8:30 p.m., and he’d have just a few hours of free time before lights off. three months in, he got a letter from united states citizenship and immigration services. “they had closed my case and taken away my work permit,” he said. “they pretty much told me, ‘we can’t have you here because of your problems.’”. maldonado was born in mexico and came to the u.s. when he was 8 years old. as a teenager he’d been granted four years of work authorization, and along with that, a driver’s license and a social security card. but after multiple minor in possession charges and then his dui, those were gone. “they won’t deport me but [they will] tell me it’s unlawful for me to be here,” he said. “i felt really bad because my parents had put a lot of money and work into getting me residency. i wanted to drink to numb the pain.”. he turned to his sponsor and arc staff members who “told me it would all be ok and supported me.”. in time, he can reapply for resident status, but he’ll have to build a case before he does, and there’s no guarantee the answer will be any different. essentially, remaining sober is pivotal if he is to gain resident status. the last month of maldonado’s stay, production manager shawn mcauley saw him really hone in on his recovery. “he realized this was a life or death thing and that he really needed to grab this program firmly and take it very seriously,” mcauley said. maldonado cites his faith as a key factor in his recovery now that he’s out of the program and living back at home with his parents. “i’ve always believed in god, but i was never as religious,” he said. “i never really prayed—just at times like ‘please don’t let me crash,’ and ‘please, don’t let me get pulled over.’ after i got [to the arc] i started seeing how other people perceived god and that you can’t use god like that.”. he keeps a book the arc chaplain gave to him called “serenity: a companion for twelve step recovery,” along with his bible and a book by pastor joel osteen called “your best life now.”. “this book…restored my faith and helped me give it to god,” he said. “it gave me positive thinking and a different outlook on life with god in it, which i really needed. i was very negative there for a while.”. life hasn’t been perfect since he returned home in mid-november. his stepfather lost his job, and while he’s since found work again, it was hard on the family. meanwhile maldonado, who wants to work to help pay the bills, hasn’t been able to since his status is now illegal. he watches his younger siblings, ages 1 and 8, two days a week when his mother is at work. at the time of this interview it’d been about six weeks since he completed the program, one of 79 men who did, out of 343 male intakes to the program in 2015, according to struck. the completion rate is 23 percent for men, about 10 percent above the national average. “this program is very successful for those who engage it,” mcauley said. “i think if aaron wants to [stay sober] he will. he’s learned everything he needs to know about managing recovery.”. maldonado has changed his friends so he’s not tempted to drink or use drugs. he goes to aa meetings every saturday in vail and keeps in touch with his sponsor. he also wants to start volunteering at the local salvation army vail valley chapter, in part because he learned before leaving the arc that if he stayed connected with the salvation army for the first year after rehab, the chance of staying sober increases greatly. every night he reads a chapter in the bible and a chapter in the osteen book before bed and he prays. “i believe that god has a plan for my life,” he said. “i can’t lose my faith now. i don’t want to go back to drinking and drugs.”.

Open context player

Close context player

Plays:-Audio plays count

unscathed. aaron varela maldonado after dui, teen’s legal residency hinges on sobriety. drunk and high on cocaine, aaron varela maldonado climbed into the driver’s seat of his car with a friend riding shotgun in late january 2015. with neither passenger buckled in, maldonado lost control of the vehicle and missed a sharp turn, crashing into a tree in vail, colo. though neither wore a seatbelt, they emerged relatively unscathed. but even the crash, spending the night in jail, and being charged with a dui wasn’t enough to make him stop using drugs. it all started when maldonado first tried drugs at 15 years old. it wasn’t a sip of beer or a puff on a joint. it was crack cocaine, given to him by his uncle, which sparked a seven-year drug and alcohol habit. by age 17, maldonado’s mother and stepfather were finding weed pipes and liquor bottles in his drawers. he’d often come home with his face bloodied from fights. “they knew i was out of control,” he said. “they kicked me out a few times but they’d always take me back. and i never stopped using.”. his mom and stepfather finally asked him, “why are you always drunk?”. “i told them, ‘i can’t stop,’” he said. maldonado learned of the adult rehabilitation center (arc) in denver, a facility run by the salvation army that provides low-cost and free treatment to those in need. everyone is welcome, so long as they are willing to participate in the biblically based program and work to fund their stay. though initially reluctant, maldonado applied and was accepted. april 17, 2015, marked his first day in the program. “i never tried to quit an addiction before,” he said. “i heard all of these people talking about what it was like when they were using. i started looking for a sponsor.”. and then, just two weeks in, he got terrible news. his cousin had died during an epileptic seizure. at first, he just wanted to leave, he said. but instead the program supervisors gave him a pass to go to the funeral. “at that moment, everyone found out and started supporting me,” he said. “people who didn’t know me came up and gave me a hug. right there, my second week, i started feeling like i didn’t need a substance to make me feel better. the support was incredible.”. when he returned from the funeral, he took a breathalyzer test and a urinalysis, both of which he passed. it was a milestone. “the program is six months long and we find that the first 30 days are the most critical in the success of a beneficiary,” said lt. allison struck, who runs the arc along with her husband. soon, the strict routine felt like home, maldonado said. the days started with breakfast at 5:30 a.m., followed by morning devotions before heading to work at the arc warehouse where he’d help sort donations for four arc thrift stores. after work, maldonado would sneak a shower in before dinner, which was followed by classes like rehab issues, anger management and relapse prevention. after class, he attended bible study and an alcohol anonymous (aa) meeting. the meetings ended at 8:30 p.m., and he’d have just a few hours of free time before lights off. three months in, he got a letter from united states citizenship and immigration services. “they had closed my case and taken away my work permit,” he said. “they pretty much told me, ‘we can’t have you here because of your problems.’”. maldonado was born in mexico and came to the u.s. when he was 8 years old. as a teenager he’d been granted four years of work authorization, and along with that, a driver’s license and a social security card. but after multiple minor in possession charges and then his dui, those were gone. “they won’t deport me but [they will] tell me it’s unlawful for me to be here,” he said. “i felt really bad because my parents had put a lot of money and work into getting me residency. i wanted to drink to numb the pain.”. he turned to his sponsor and arc staff members who “told me it would all be ok and supported me.”. in time, he can reapply for resident status, but he’ll have to build a case before he does, and there’s no guarantee the answer will be any different. essentially, remaining sober is pivotal if he is to gain resident status. the last month of maldonado’s stay, production manager shawn mcauley saw him really hone in on his recovery. “he realized this was a life or death thing and that he really needed to grab this program firmly and take it very seriously,” mcauley said. maldonado cites his faith as a key factor in his recovery now that he’s out of the program and living back at home with his parents. “i’ve always believed in god, but i was never as religious,” he said. “i never really prayed—just at times like ‘please don’t let me crash,’ and ‘please, don’t let me get pulled over.’ after i got [to the arc] i started seeing how other people perceived god and that you can’t use god like that.”. he keeps a book the arc chaplain gave to him called “serenity: a companion for twelve step recovery,” along with his bible and a book by pastor joel osteen called “your best life now.”. “this book…restored my faith and helped me give it to god,” he said. “it gave me positive thinking and a different outlook on life with god in it, which i really needed. i was very negative there for a while.”. life hasn’t been perfect since he returned home in mid-november. his stepfather lost his job, and while he’s since found work again, it was hard on the family. meanwhile maldonado, who wants to work to help pay the bills, hasn’t been able to since his status is now illegal. he watches his younger siblings, ages 1 and 8, two days a week when his mother is at work. at the time of this interview it’d been about six weeks since he completed the program, one of 79 men who did, out of 343 male intakes to the program in 2015, according to struck. the completion rate is 23 percent for men, about 10 percent above the national average. “this program is very successful for those who engage it,” mcauley said. “i think if aaron wants to [stay sober] he will. he’s learned everything he needs to know about managing recovery.”. maldonado has changed his friends so he’s not tempted to drink or use drugs. he goes to aa meetings every saturday in vail and keeps in touch with his sponsor. he also wants to start volunteering at the local salvation army vail valley chapter, in part because he learned before leaving the arc that if he stayed connected with the salvation army for the first year after rehab, the chance of staying sober increases greatly. every night he reads a chapter in the bible and a chapter in the osteen book before bed and he prays. “i believe that god has a plan for my life,” he said. “i can’t lose my faith now. i don’t want to go back to drinking and drugs.”.

Listen to this article