Listen to this article

Listen to this article

Loading

Play

Pause

Options

0:00

-:--

1x

Playback Speed- 0.5

- 0.6

- 0.7

- 0.8

- 0.9

- 1

- 1.1

- 1.2

- 1.3

- 1.5

- 2

Audio Language

- English

- French

- German

- Italian

- Spanish

Open text

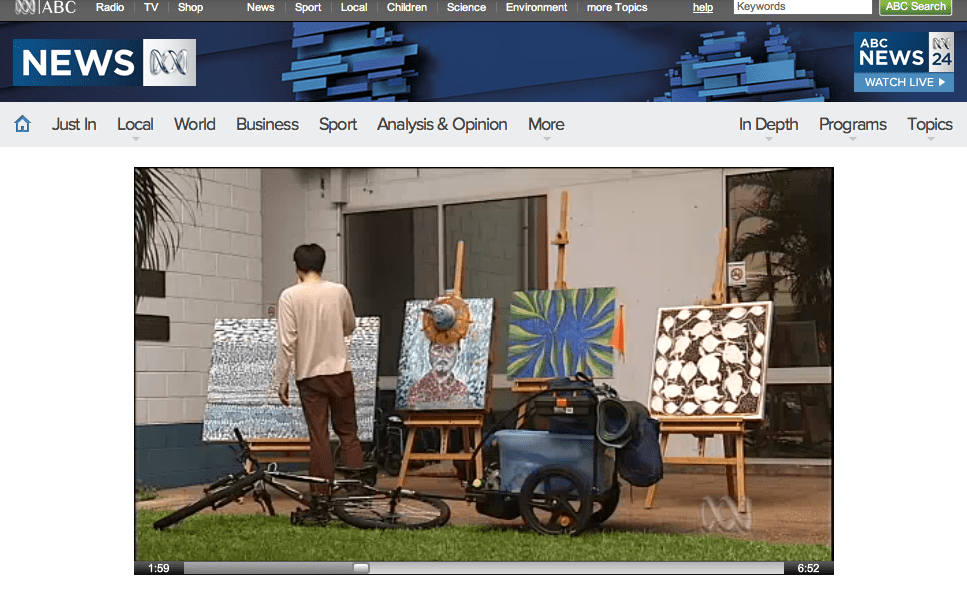

studio on the street. one fateful morning, a woman from a comfortable financial background entered the the salvation army life centre in darwin, australia, full of curiosity and interest. she confidently eyed her surroundings, continuously praising our art therapy class for people experiencing homelessness. at the end of her guided tour of the facility, i casually directed her attention to some of the paintings they had done that were hanging on our dreary walls and shared my wish to create an alternative space on the street foyer of the life centre. her eyes lit up. she had her own collection of paintings, she said. the next thing i knew, i was walking with her to the nearest atm listening to her excited words. “i want to help you,” she said. “i want to give a donation.”. up until this moment, i had a $500 annual budget for paints and canvases that lasted only six months. when i took over the coordination of the life centre, art activities had to be pushed to the back burner for the more immediate needs of food, drink and shelter. however, a number of artists continued to express a desire and interest in painting, so i found myself scrounging up leftovers of past project activities. i brainstormed ways to engage the more creative side of our visitors and friends. by this time, our numbers had risen from 25 to 35 individuals daily. as a result, i had to look into making use of the street side of the life centre to accommodate art activities. when the woman making the donation and i made it to the atm, the machine spit out bill after dollar bill until she had withdrawn $500, which she handed to me. dumbfounded, i stashed the bills into my pocket. then, she repeated the whole process. she stopped, turned to me and said, “now is that enough—$1,000?” i did not know what to say. i smiled, nervously keeping my hand in my pocket to make sure all the money was safe. that donation allowed us to change gears and create “studio on the street.” what followed was a small grant from the northern territory office of the arts, private donations including one from the mayor of darwin, sales from random buyers on the street, an exhibit at the darwin city council art space and television feature on the australian broadcasting corporation (abc) network. watch a feature of studio on the street at since our numbers increased to 80 individuals per day, we began using a borrowed office space at the red shield hostel as a temporary art studio. however, the street continues to be our gallery. mick ross, a volunteer of the life centre and lead artist of studio on the street, embodies the true essence of the project. “i’ve always had a love for painting,” ross said. “just the act of painting inspires me to paint. it helps me through the low times. sometimes it’s the only thing there for me, like an old friend that’s always there to give a hand.”. studio on the street is a positive outlet for individuals experiencing homelessness. it empowers those who have lost everything and restores dignity in showcasing their talents. not to mention, 90 percent of the sale of every painting goes directly to the artist. ross yuldjirri, a painter involved in the program, was trained by his uncle, world famous painter thompson yuldjirri. ross yuldjirri said he is homeless and has abused alcohol for many years. “painting is an expression of my feeling to care for someone else,” he said. like its artists, studio on the street survives one day and one donation at a time. yet, this project represents that glimmer of hope, that hope for change, that change toward a new life––all the reasons the life centre was created. and while these artists struggle through their brokenness, i hope they continue to find a sense of wholeness through studio on the street.

Open context player

Close context player

Plays:-Audio plays count

studio on the street. one fateful morning, a woman from a comfortable financial background entered the the salvation army life centre in darwin, australia, full of curiosity and interest. she confidently eyed her surroundings, continuously praising our art therapy class for people experiencing homelessness. at the end of her guided tour of the facility, i casually directed her attention to some of the paintings they had done that were hanging on our dreary walls and shared my wish to create an alternative space on the street foyer of the life centre. her eyes lit up. she had her own collection of paintings, she said. the next thing i knew, i was walking with her to the nearest atm listening to her excited words. “i want to help you,” she said. “i want to give a donation.”. up until this moment, i had a $500 annual budget for paints and canvases that lasted only six months. when i took over the coordination of the life centre, art activities had to be pushed to the back burner for the more immediate needs of food, drink and shelter. however, a number of artists continued to express a desire and interest in painting, so i found myself scrounging up leftovers of past project activities. i brainstormed ways to engage the more creative side of our visitors and friends. by this time, our numbers had risen from 25 to 35 individuals daily. as a result, i had to look into making use of the street side of the life centre to accommodate art activities. when the woman making the donation and i made it to the atm, the machine spit out bill after dollar bill until she had withdrawn $500, which she handed to me. dumbfounded, i stashed the bills into my pocket. then, she repeated the whole process. she stopped, turned to me and said, “now is that enough—$1,000?” i did not know what to say. i smiled, nervously keeping my hand in my pocket to make sure all the money was safe. that donation allowed us to change gears and create “studio on the street.” what followed was a small grant from the northern territory office of the arts, private donations including one from the mayor of darwin, sales from random buyers on the street, an exhibit at the darwin city council art space and television feature on the australian broadcasting corporation (abc) network. watch a feature of studio on the street at since our numbers increased to 80 individuals per day, we began using a borrowed office space at the red shield hostel as a temporary art studio. however, the street continues to be our gallery. mick ross, a volunteer of the life centre and lead artist of studio on the street, embodies the true essence of the project. “i’ve always had a love for painting,” ross said. “just the act of painting inspires me to paint. it helps me through the low times. sometimes it’s the only thing there for me, like an old friend that’s always there to give a hand.”. studio on the street is a positive outlet for individuals experiencing homelessness. it empowers those who have lost everything and restores dignity in showcasing their talents. not to mention, 90 percent of the sale of every painting goes directly to the artist. ross yuldjirri, a painter involved in the program, was trained by his uncle, world famous painter thompson yuldjirri. ross yuldjirri said he is homeless and has abused alcohol for many years. “painting is an expression of my feeling to care for someone else,” he said. like its artists, studio on the street survives one day and one donation at a time. yet, this project represents that glimmer of hope, that hope for change, that change toward a new life––all the reasons the life centre was created. and while these artists struggle through their brokenness, i hope they continue to find a sense of wholeness through studio on the street.

Listen to this article