Listen to this article

Listen to this article

Loading

Play

Pause

Options

0:00

-:--

1x

Playback Speed- 0.5

- 0.6

- 0.7

- 0.8

- 0.9

- 1

- 1.1

- 1.2

- 1.3

- 1.5

- 2

Audio Language

- English

- French

- German

- Italian

- Spanish

Open text

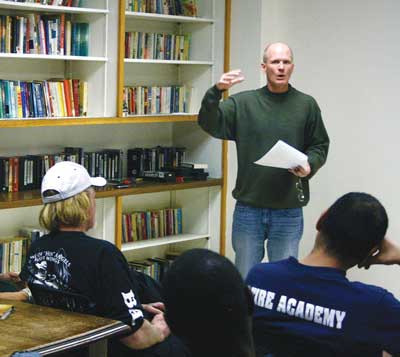

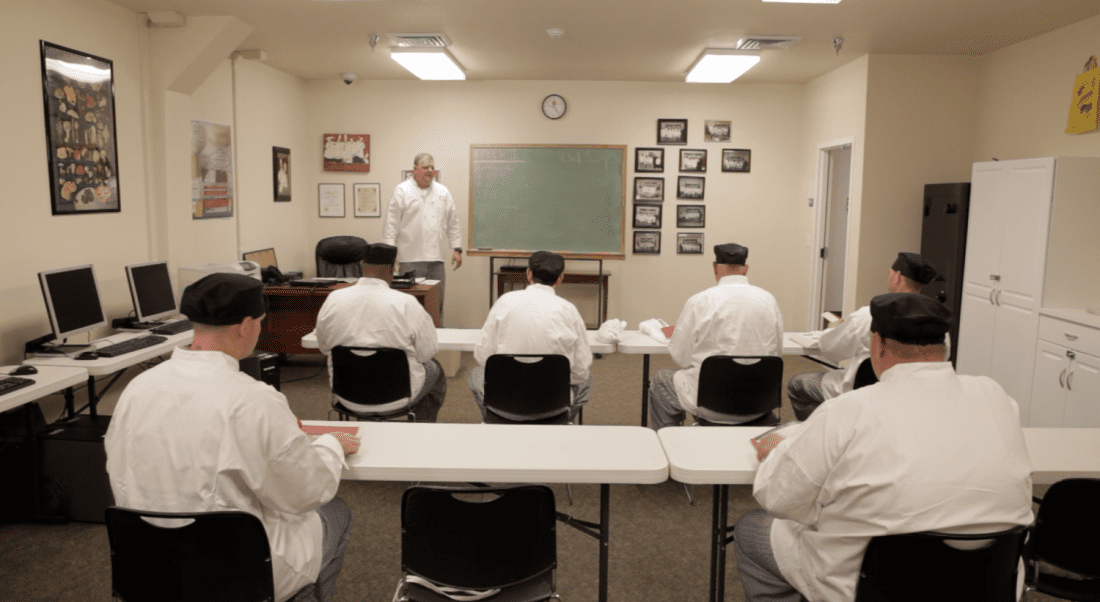

shelter from the cold. escapingconditions andfinding community at crossroads. by josiah hesse. whenever a deep-sea diver travels too deep into the water, it’s essential that he come back up slowly. if he ascends too quickly he’ll suffer from the bends, a trauma that requires therapy in a recompression chamber. similarly, the chronically homeless often have trouble dealing with transitioning from the independent yet insecure life of the street to the responsibilities and consistencies of a home and job. they need to come up gradually under the right conditions, and trying to manage a compression chamber filled with 300 men all in different stages of that process requires a delicate and nuanced director. “there are guys who will come here and stay for a week or a month and leave, and then there are those who will stay for a year or more,” says carlton jackson, manager of the salvation army crossroads shelter for men in denver. “but those guys who stay will often be the more stable part of the population.”. carlton explains that there are three residency levels at crossroads. the unestablished newcomers will wait in line outside the building at 4 p.m., and will have the opportunity to sleep on floormats along with up to 160 other men (along with a meal, shower, tv and library). from there they can get on the list for a bed and a locker at $42 a week, spread out army-barracks style across one large room. eventually they can enroll in crossroads newly minted stepping up program, which offers fitness and financial planning classes, as well as a room of their own on the second floor. jackson stresses that something like a bed and a secure locker are not only practical necessities, but are essential in aiding a homeless individual in the delicate transition. “the psychological and the practical go hand in hand,” he says. “if you’re trying to get yourself into the regular world and you’ve got all your belongings on your back, it’s hard to get yourself mentally prepared and show up for a job interview. with a bed and a locker you can leave your stuff here and go out and tackle things. unfortunately we only have so much room, so those staying on mats have to take their stuff with them.”. those sleeping for free on mats are required to leave at 6 a.m., while the patrons of rented beds can sleep in later—though many of them are out by four or five, heading to day labor offices where they wait in another line, hoping to get work that will cover the cost of their bed. after spending five years incarcerated for burglary, mike has spent the last two months at crossroads, working at a carwash to pay for his bed, a court-ordered restitution, and hopefully a little savings in time. “i became a christian minister while i was incarcerated,” he says. “and staying here is a good stepping stone; a good foundation. i want to start my own ministry going to disaster sites, helping communities rebuild.”. and he’s getting plenty of first-hand exposure to disaster relief while here. mike says that the chaos of those sleeping on the mats is notably different from the stable consistency of those renting the beds. lately he’s become acquainted with ty, carlos and “uncle” ray, three long-term residents who are part of the community that has developed between the roommates of crossroads. after staying here for a year, ty says that moving up to the beds “gives you a sense that there will be a next step, a next phase. when you’re sleeping on the mats staring at the ceiling, you feel trapped, like it’s never going to end.”. despite graduating from cornell university, employment and financial issues led to ty to becoming homeless, which jackson says is well-tread road to the shelter’s doorstep. “joblessness is the biggest unifier here,” he says. “there are others, like mental illness, drug and alcohol addiction, incarceration, but at the end of the day it’s the inability to get and hold onto work.”. jackson says the bed population have formed a community that networks with each other. “last year there was a time when denver’s waste management had been using day-labor, and some people were informed about permanent jobs opening up there,” he says. “and the guys here who got the tip would tell other people they trusted, and there was a wave of employment throughout the shelter.”. at the same time, trying to keep that community together with up to 260 men dealing with various addictions, illnesses and unfortunate backgrounds under one roof is a tricky juggling act. just before dinner, an argument ensues between some residents over the tv—one wants the news, the other wants the broncos. jackson knows each of them by name, and gracefully cracks some jokes and gets everyone laughing, neutralizing what he knows from experience had the potential to be a fight. earlier in the year carlos was assaulted during an argument in the courtyard, resulting in a broken jaw that required surgery. having grown up around hell’s angels and being homeless since the age of 14, carlos says he “didn’t want to be a snitch. carlton kept asking me ‘who did this to you?’ but i told him not to worry about it. but then i was gonna get kicked out for not saying who it was.”. “i didn’t want to put you in that position,” jackson says, speaking to carlos about the incident. “but the bottom line is we can’t have that here. if there’s someone here who’s willing to assault other people, you’re not going to be the last one he hits.”. jackson has the ability to empathize and communicate with the residents of crossroads because it wasn’t long ago that he was in their shoes. along with half of the shelter’s staff, jackson found his way into employment with the salvation army through first being one of its clients. “they get a different perspective,” says ty of staff members who once lived here. “when things go down, they can say ‘hey, you know what’s going to happen,’ and it doesn’t feel like it’s authoritative, it’s like it’s coming from one of your friends.”. scott fingers was never a resident of crossroads, and up until a few months ago he had a secure job in healthcare, but then he says that “the lord called me into ministry. and when i saw that salvation army was a christian, evangelistic organization, i knew it was for me.”. fingers is now head of crossroads’ stepping up program, which is the third level of residency available to those staying at the shelter. involvement in the program requires a structured lifestyle of strict sobriety, employment and consistent attendance of church services (though this is not limited to christian churches). “the goal of stepping up is to get people back into the mainstream,” he says. “after they’re sober and attending church, we then help them get a job, and once they’re employed they get a room on the second floor. they pay 25 percent of their income to us for rent, they save 50 percent toward a down-payment on an apartment, and the remainder is theirs. and while they’re up here we provide classes on things like how to build a budget, anger-management, fitness.”. the program can only admit 25 men at a time, and they are allowed to stay on the second floor for three to six months. the shelter already has to turn people away when it reaches its capacity of 260 bodies, and between the record low temperatures (on dec. 4 the wind chill was recorded at -31 degrees), and a report from the metro denver homeless initiative that the city is enduring an influx of homeless from surrounding counties, the staff has had its hands full keeping things calm and optimistic at crossroads. “at the end of the day it’s about resource allocation,” says jackson. “unfortunately there’s a much bigger need than the resources that we have. so we have to find a fair, compassionate way to apply those resources, and a firm hand when we’re out. when we’re full and don’t have beds, it’s very hard to face a man and turn him away. but we know from past experiences that when we take in 10 extra guys it leads to problems like not enough food, no space, and before you know it the police are here. when we create stability and safety, a community forms, which is just human nature; it’s what we do.”.

Open context player

Close context player

Plays:-Audio plays count

shelter from the cold. escapingconditions andfinding community at crossroads. by josiah hesse. whenever a deep-sea diver travels too deep into the water, it’s essential that he come back up slowly. if he ascends too quickly he’ll suffer from the bends, a trauma that requires therapy in a recompression chamber. similarly, the chronically homeless often have trouble dealing with transitioning from the independent yet insecure life of the street to the responsibilities and consistencies of a home and job. they need to come up gradually under the right conditions, and trying to manage a compression chamber filled with 300 men all in different stages of that process requires a delicate and nuanced director. “there are guys who will come here and stay for a week or a month and leave, and then there are those who will stay for a year or more,” says carlton jackson, manager of the salvation army crossroads shelter for men in denver. “but those guys who stay will often be the more stable part of the population.”. carlton explains that there are three residency levels at crossroads. the unestablished newcomers will wait in line outside the building at 4 p.m., and will have the opportunity to sleep on floormats along with up to 160 other men (along with a meal, shower, tv and library). from there they can get on the list for a bed and a locker at $42 a week, spread out army-barracks style across one large room. eventually they can enroll in crossroads newly minted stepping up program, which offers fitness and financial planning classes, as well as a room of their own on the second floor. jackson stresses that something like a bed and a secure locker are not only practical necessities, but are essential in aiding a homeless individual in the delicate transition. “the psychological and the practical go hand in hand,” he says. “if you’re trying to get yourself into the regular world and you’ve got all your belongings on your back, it’s hard to get yourself mentally prepared and show up for a job interview. with a bed and a locker you can leave your stuff here and go out and tackle things. unfortunately we only have so much room, so those staying on mats have to take their stuff with them.”. those sleeping for free on mats are required to leave at 6 a.m., while the patrons of rented beds can sleep in later—though many of them are out by four or five, heading to day labor offices where they wait in another line, hoping to get work that will cover the cost of their bed. after spending five years incarcerated for burglary, mike has spent the last two months at crossroads, working at a carwash to pay for his bed, a court-ordered restitution, and hopefully a little savings in time. “i became a christian minister while i was incarcerated,” he says. “and staying here is a good stepping stone; a good foundation. i want to start my own ministry going to disaster sites, helping communities rebuild.”. and he’s getting plenty of first-hand exposure to disaster relief while here. mike says that the chaos of those sleeping on the mats is notably different from the stable consistency of those renting the beds. lately he’s become acquainted with ty, carlos and “uncle” ray, three long-term residents who are part of the community that has developed between the roommates of crossroads. after staying here for a year, ty says that moving up to the beds “gives you a sense that there will be a next step, a next phase. when you’re sleeping on the mats staring at the ceiling, you feel trapped, like it’s never going to end.”. despite graduating from cornell university, employment and financial issues led to ty to becoming homeless, which jackson says is well-tread road to the shelter’s doorstep. “joblessness is the biggest unifier here,” he says. “there are others, like mental illness, drug and alcohol addiction, incarceration, but at the end of the day it’s the inability to get and hold onto work.”. jackson says the bed population have formed a community that networks with each other. “last year there was a time when denver’s waste management had been using day-labor, and some people were informed about permanent jobs opening up there,” he says. “and the guys here who got the tip would tell other people they trusted, and there was a wave of employment throughout the shelter.”. at the same time, trying to keep that community together with up to 260 men dealing with various addictions, illnesses and unfortunate backgrounds under one roof is a tricky juggling act. just before dinner, an argument ensues between some residents over the tv—one wants the news, the other wants the broncos. jackson knows each of them by name, and gracefully cracks some jokes and gets everyone laughing, neutralizing what he knows from experience had the potential to be a fight. earlier in the year carlos was assaulted during an argument in the courtyard, resulting in a broken jaw that required surgery. having grown up around hell’s angels and being homeless since the age of 14, carlos says he “didn’t want to be a snitch. carlton kept asking me ‘who did this to you?’ but i told him not to worry about it. but then i was gonna get kicked out for not saying who it was.”. “i didn’t want to put you in that position,” jackson says, speaking to carlos about the incident. “but the bottom line is we can’t have that here. if there’s someone here who’s willing to assault other people, you’re not going to be the last one he hits.”. jackson has the ability to empathize and communicate with the residents of crossroads because it wasn’t long ago that he was in their shoes. along with half of the shelter’s staff, jackson found his way into employment with the salvation army through first being one of its clients. “they get a different perspective,” says ty of staff members who once lived here. “when things go down, they can say ‘hey, you know what’s going to happen,’ and it doesn’t feel like it’s authoritative, it’s like it’s coming from one of your friends.”. scott fingers was never a resident of crossroads, and up until a few months ago he had a secure job in healthcare, but then he says that “the lord called me into ministry. and when i saw that salvation army was a christian, evangelistic organization, i knew it was for me.”. fingers is now head of crossroads’ stepping up program, which is the third level of residency available to those staying at the shelter. involvement in the program requires a structured lifestyle of strict sobriety, employment and consistent attendance of church services (though this is not limited to christian churches). “the goal of stepping up is to get people back into the mainstream,” he says. “after they’re sober and attending church, we then help them get a job, and once they’re employed they get a room on the second floor. they pay 25 percent of their income to us for rent, they save 50 percent toward a down-payment on an apartment, and the remainder is theirs. and while they’re up here we provide classes on things like how to build a budget, anger-management, fitness.”. the program can only admit 25 men at a time, and they are allowed to stay on the second floor for three to six months. the shelter already has to turn people away when it reaches its capacity of 260 bodies, and between the record low temperatures (on dec. 4 the wind chill was recorded at -31 degrees), and a report from the metro denver homeless initiative that the city is enduring an influx of homeless from surrounding counties, the staff has had its hands full keeping things calm and optimistic at crossroads. “at the end of the day it’s about resource allocation,” says jackson. “unfortunately there’s a much bigger need than the resources that we have. so we have to find a fair, compassionate way to apply those resources, and a firm hand when we’re out. when we’re full and don’t have beds, it’s very hard to face a man and turn him away. but we know from past experiences that when we take in 10 extra guys it leads to problems like not enough food, no space, and before you know it the police are here. when we create stability and safety, a community forms, which is just human nature; it’s what we do.”.

Listen to this article