Diversionary program helps low-level offenders work toward self-sufficiency

Stephen Killebrew trolled the streets of Santa Barbara, Calif., drunk and high on synthetic marijuana. He’d been homeless three years, and throttled by schizophrenia and bipolar disorder for even longer. On this particular night, he shouted expletives at passing traffic, fuming for no apparent reason. One man driving by noticed Killebrew was out of sorts, so he pulled up and offered his help.

Things escalated from there, and Killebrew punched the man in the face. Normally, this type of situation may have sorted itself out, but the stranger Killebrew assaulted happened to be an on-duty Santa Barbara police officer.

“I had smoked some spice, and I was out of my mind,” Killebrew recalled.

Fast-forward 15 months—Killebrew’s clean shaven, donning a paisley button-up shirt in Department Seven of Santa Barbara’s Superior Court. He’s served one year in county jail for the altercation, and he’s trying to get his arrest record cleared entirely. He addresses presiding Judge Thomas Adams.

“Stephen,” Adams said, glancing up at him, “I hear you’re doing well.”

“That’s right, your honor,” Killebrew said, nearly cutting him off. “I’m staying sober, and I actually just got a job. I start on Sunday.”

“That’s great,” Adams said with relief. “Keep going.”

Killebrew, 53, is on track to have his case dismissed this summer. He just has to report in on his status at the court every other Thursday for six months, he has to stay sober, and he has to stay out of additional trouble.

“Long as I stay clean, I’m never going to get in trouble,” Killebrew said.

It’s all part of Restorative Court, a jail diversionary program for chronic offenders of minor municipal and state codes often linked to homelessness—offenses such as public intoxication, illegal lodging, and drunk and disorderly conduct that stuff court calendars and monopolize police resources.

In Restorative Court’s four years, 180 people have graduated from the program, 66 have been housed, and 335 have been placed in programs other than shelters. Some have even reunited with family members.

The program is typically reserved for chronically homeless individuals with an extensive history of mental illness or substance abuse—often together—who’ve committed infractions and misdemeanors. But according to Santa Barbara Restorative Police Officer Craig Burleigh, it tends to show leniency to those who’ve committed more serious offenses as a byproduct of drugs or alcohol or mental illness, as in Killebrew’s case.

“If it’s a felony because he’s an addict of drugs or alcohol, and he went to CVS and stole a bottle of Jack Daniels, then I’ll take that even though it’s a felony,” he said, “because I can say there’s a causation—he stole the alcohol because he’s an alcoholic.”

It all started in 2011, when former Commissioner Pauline Maxwell and Restorative Police Officer Keld Hove were brainstorming ways for the city to both cut costs and address the complicated needs of its chronically homeless population. With concern mounting from several local businesses over the high incidences of panhandling, trespassing and petty theft, they got to work and organized a panel of community service providers to do just that.

Mureen Brown, outreach specialist for the Santa Barbara Police Department, said the program’s come a long way since then, but it’s still just as necessary now.

“We have 1,600 homeless people in Santa Barbara. Everyone wants to come to Santa Barbara because it’s beautiful here,” she said. “Many people that come here feel that they just have a right to live here.”

Mark Gisler, executive director of The Salvation Army Hospitality House, which houses many Restorative Court clients, said another challenge is adapting to the changing face of those they serve.

“We’re seeing far more cases of mental health now than we were five years ago,” he said.

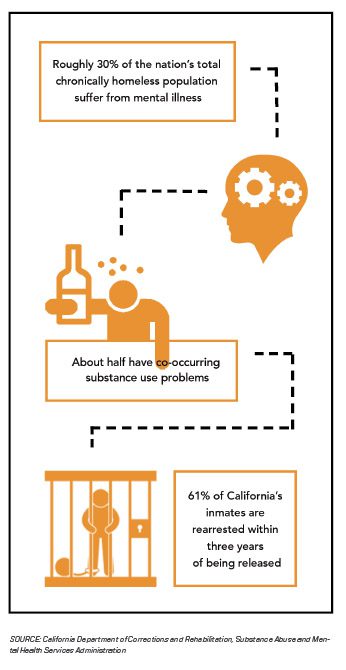

The mentally ill homeless—which account for roughly 30 percent of the nation’s total chronically homeless population—can be some of the most difficult to reach, often self-medicating with drugs and alcohol. This, he said, underscores the value in wraparound case management. Providing the full spectrum of services to clients typically makes for a more seamless transition once they move on, he added, as self-sufficiency is the ultimate goal of the program.

Some clients, such as Killebrew, needed almost every one of these resources. After stabilizing at the The Department of Alcohol, Drug, and Mental Health Services CARES facility, he was referred to the Hospitality House, a 70-bed transitional living program designed to help homeless men and women secure and maintain income and permanent housing,

“I came in [Hospitality House] with no ID, no birth certificate, no Social Security card,” he said. “Since that time, I’ve been getting medical support, food stamps, a driver’s license. I’ve even reconnected with my family.

“If they wouldn’t have pointed me to CARES, I never would have gotten to The Salvation Army. Without The Salvation Army, I wouldn’t have had an address for them to send my birth certificate to,” he said. “Without my birth certificate, I wouldn’t have been able to get my ID. Without my ID, I couldn’t have gotten a Social Security card. Without the Social Security card, I wouldn’t be able to work. This ID was critical. If you don’t have the ID, it stops you dead in your tracks.”

Santa Barbara Mayor Helene Schneider, who counts herself among the program’s biggest advocates, said that beyond the value of the services offered, it’s pivotal that the chronically homeless population see “the other side” of law enforcement.

“They need that boost or encouragement, as opposed to only seeing law enforcement as an enforcement agency that only tells them they’re doing something wrong,” said Schneider, who’s also running for California’s 24th Congressional District seat. “It’s a totally different way of interacting with the court system and with law enforcement, and that makes a big difference in how people participate.”

According to Brown, the program has drawn interest from officials in Santa Maria, Oxnard, San Diego, San Jose, and parts of Los Angeles, among others. She said the biggest challenge they face in adapting the program is forging a link between their police departments and the courts, because “it doesn’t normally work that way.”

Schneider insisted it starts with political will.

“You need your [city] council and your senior management and your police chief to say ‘This is important,’” she said. “This type of work is police work. [Police work] is not just writing tickets and telling people to move along. It’s actually solving the problem.”

From there, you need the buy-in from key stakeholders willing to pool their resources for the greater good.

“I’m just appreciative that organizations like The Salvation Army are willing to work with government agencies, other social services agencies, the business community, law enforcement, and focus on getting the job done,” she said. “The trick is, we each have our own strengths, but it’s challenging to sometimes let go and let other agencies do what they can do without telling them how to do it. That collaborative is important and necessary and very difficult, so when it works, it’s fantastic.”

After completing 75 days in the program, Stephen was offered housing and a job opportunity with family out of state. Now with a new job, permanent housing, and continued sobriety, Stephen is considered a Hospitality House success story.

When he considers a life without Restorative Court, he’s grateful.

“Restorative court was a good thing for me, and it could be a good thing for other people—it depends on what they’re willing to do,” he said. “If they’re willing to follow the rules, stay out of trouble, report in, it’s a gold mine. Literally. It’s a gold mine for resources.”