Listen to this article

Listen to this article

Loading

Play

Pause

Options

0:00

-:--

1x

Playback Speed- 0.5

- 0.6

- 0.7

- 0.8

- 0.9

- 1

- 1.1

- 1.2

- 1.3

- 1.5

- 2

Audio Language

- English

- French

- German

- Italian

- Spanish

Open text

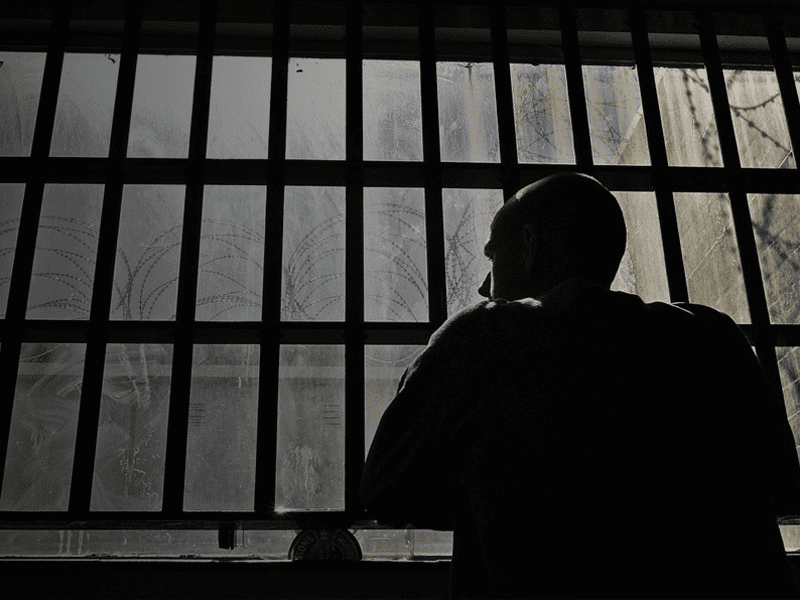

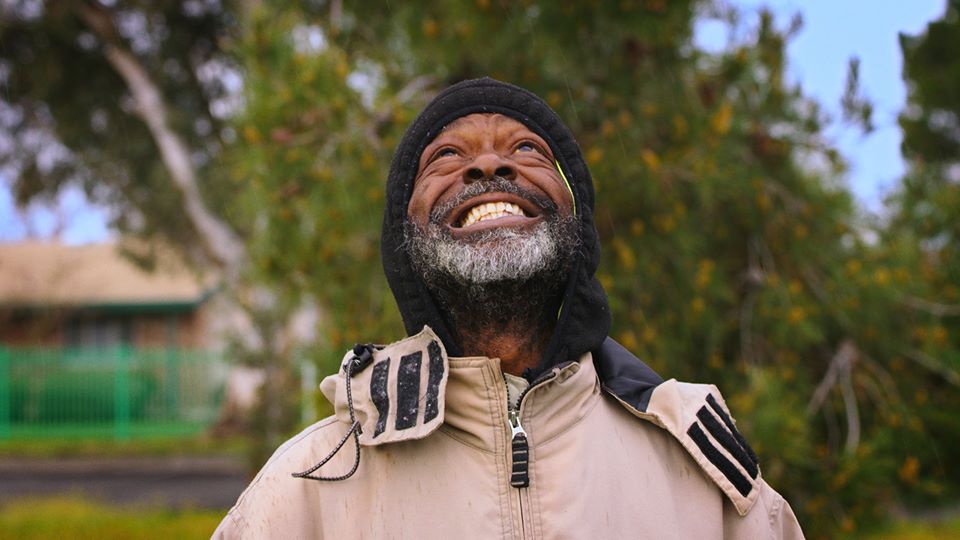

reframing how we talk about service. the social services sector aims to transform how the public sees it, and garner the support it needs to grow. widely hailed “the father of broadcasting,” david sarnoff broadcasted the first ever live sporting event on the radio. and in doing so, he shifted the way the public thought about the radio. it went from being “a large, expensive eyesore that delivers the news” to “the box that brings the world to your living room.”. now, imagine if the social services sector could reframe itself in a similar way—transforming how the public sees it, and garnering the support it needs to grow into the force it was always destined to become. as the president and ceo of the national human services assembly (nhsa), lee sherman is well connected to leaders of organizations doing good in communities across the country. the washington, d.c.-based association advocates for over 80 of the largest national nonprofits, including the salvation army, boys and girls clubs of america, volunteers of america and more. having existed for about 95 years, the nhsa aims to be a voice for the social services sector as a whole. in recent years, amid funding cuts and stagnating charitable giving, the nhsa realized that the value and rich potential of human services is simply not resonating with the public, sherman said. so it prompted a national reframing initiative to build deeper public backing for human services. “when we support well-being, we make sure that everyone can reach their potential and fully contribute to our communities,” sherman said. “in turn, maximizing potential helps our communities to thrive and remain vibrant.”. with the frameworks institute, a national nonprofit think tank that frames public issues to bridge the divide between public and expert understanding, the nhsa developed an evidence-based strategy for human services. “well-being is built,” he said. “just as building a strong house requires a variety of materials, building well-being requires community resources, social relationships, and opportunities to thrive. to build well-being in our community depends on many people working together, just as building a house does.”. sherman recently sat down with caring to share more about the initiative to reframe how we talk about service. how did the national reframing initiative come about? we’ve seen in organizations across the sector that needs continue to increase whereas resources—philanthropic, government, fee per service, and so on—don’t necessarily match. so we wondered, is there a disconnect that not everyone sees the need to contribute or support these kinds of services? that led to the idea that we needed to do evidence-based research to find out what language we’re using and if the public was responding to it in the way we intended. we received grant funding and hired frameworks institute to do the study, fieldwork and interviews to determine what people respond to. it’s clear from that work that there’s always a disconnect in what the experts say and what the public hears or understands. it comes from the cultural models we all hold and the way our brain works that when we don’t understand something, our brain fills the void. it fills in those spaces. we wanted to create a campaign of language that would fill in those spaces for people to understand what it is we really do. how does the sector fight against ideas of the “deserving poor” versus “the lazy”? the tension revolves around assessments of the “worthiness” of a person in need, while events and contexts remain invisible. people tend to assume that those who need to be served—because of low economic conditions, or homelessness, or kids in juvenile justice, or any of the great range of issues—need help because of the person’s choices, bad choices. people in the field, experts if you will, understand that there are systems, unavailability of services, differences in education, influences of where a person lives, and so on. blaming the person is not the direction we want to go when we talk about the services we provide. research shows people respond to individual stories with what we’d call “exceptionalism,” believing a person can overcome great odds because he’s an exceptional individual. that undercuts all the help and services he had along the way—the mentor, the tutor, the financial assistance to go to college. yes, he put in the work to succeed, but creating those opportunities for anyone to fulfill their individual potential is something we do as organizations. we want to tell that story as well. we train people not to tell individual stories in the same way, but rather to talk about successes in context of the work that they do. we don’t like to talk about “vulnerable” populations; no one describes themselves as vulnerable. we like to talk about issues that surround a vulnerability—a young person with an addicted parent, for example. we have seen that the changes in framing cause positive reactions in the public and we are seeing success in fundraising campaigns. why is the reframing initiative important for the sector and society? the initiative is an opportunity for human services organizations to explain their work to the public so that they understand the critical nature and wide range of work being done. for those that adopt the frame, it’s an important part of their continued viability and opportunity to sustain themselves through funding, human capital, or public recognition of work that they do. today, there is a lot of casting of blame, and separation of “the other” instead of building stronger communities. if we can’t successfully navigate that gap, it’ll have a detrimental effect on our ability to continue to provide the services and preventive work, and shape policies that build strong communities. the reframed narrative emphasizes the broader community and the piece that we all play in that community as opposed to isolating individuals in that community. we get people thinking about how it’s not just “someone else’s” problem, but it also influences their own lives. they can be part of a community that is better off, where everyone is treated better and can be successful. how can individuals be involved in the initiative? explore the research and the toolkits online. then, the idea is to think about it as you’re communicating. think: am i talking about human potential and building well being, and not calling anybody vulnerable? the goal is for each of us to use different language. i’ve seen it work, and it’s pretty powerful. framing is a process of making choices about what to emphasize—and what to leave unsaid. instead of this…. we’re trying this…. individual benefit: helping vulnerable populations. collective benefit: fostering the human potential available to us. ladder metaphors: helping people climb out of poverty. construction metaphor: human services build well being. the triage theme: direct services address urgent needs. strands of human services theme: advocacy, planning, research, preventionanddirect services. proving the worthiness of recipients. explaining common human needs. source: national reframing initiative, national human services assembly. [button color=”black” size=”normal” alignment=”none” rel=”follow” openin=”newwindow” url=”nassembly.org/national_reframing_initiative”]see more atnational human services assembly.[/button]

Open context player

Close context player

Plays:-Audio plays count

reframing how we talk about service. the social services sector aims to transform how the public sees it, and garner the support it needs to grow. widely hailed “the father of broadcasting,” david sarnoff broadcasted the first ever live sporting event on the radio. and in doing so, he shifted the way the public thought about the radio. it went from being “a large, expensive eyesore that delivers the news” to “the box that brings the world to your living room.”. now, imagine if the social services sector could reframe itself in a similar way—transforming how the public sees it, and garnering the support it needs to grow into the force it was always destined to become. as the president and ceo of the national human services assembly (nhsa), lee sherman is well connected to leaders of organizations doing good in communities across the country. the washington, d.c.-based association advocates for over 80 of the largest national nonprofits, including the salvation army, boys and girls clubs of america, volunteers of america and more. having existed for about 95 years, the nhsa aims to be a voice for the social services sector as a whole. in recent years, amid funding cuts and stagnating charitable giving, the nhsa realized that the value and rich potential of human services is simply not resonating with the public, sherman said. so it prompted a national reframing initiative to build deeper public backing for human services. “when we support well-being, we make sure that everyone can reach their potential and fully contribute to our communities,” sherman said. “in turn, maximizing potential helps our communities to thrive and remain vibrant.”. with the frameworks institute, a national nonprofit think tank that frames public issues to bridge the divide between public and expert understanding, the nhsa developed an evidence-based strategy for human services. “well-being is built,” he said. “just as building a strong house requires a variety of materials, building well-being requires community resources, social relationships, and opportunities to thrive. to build well-being in our community depends on many people working together, just as building a house does.”. sherman recently sat down with caring to share more about the initiative to reframe how we talk about service. how did the national reframing initiative come about? we’ve seen in organizations across the sector that needs continue to increase whereas resources—philanthropic, government, fee per service, and so on—don’t necessarily match. so we wondered, is there a disconnect that not everyone sees the need to contribute or support these kinds of services? that led to the idea that we needed to do evidence-based research to find out what language we’re using and if the public was responding to it in the way we intended. we received grant funding and hired frameworks institute to do the study, fieldwork and interviews to determine what people respond to. it’s clear from that work that there’s always a disconnect in what the experts say and what the public hears or understands. it comes from the cultural models we all hold and the way our brain works that when we don’t understand something, our brain fills the void. it fills in those spaces. we wanted to create a campaign of language that would fill in those spaces for people to understand what it is we really do. how does the sector fight against ideas of the “deserving poor” versus “the lazy”? the tension revolves around assessments of the “worthiness” of a person in need, while events and contexts remain invisible. people tend to assume that those who need to be served—because of low economic conditions, or homelessness, or kids in juvenile justice, or any of the great range of issues—need help because of the person’s choices, bad choices. people in the field, experts if you will, understand that there are systems, unavailability of services, differences in education, influences of where a person lives, and so on. blaming the person is not the direction we want to go when we talk about the services we provide. research shows people respond to individual stories with what we’d call “exceptionalism,” believing a person can overcome great odds because he’s an exceptional individual. that undercuts all the help and services he had along the way—the mentor, the tutor, the financial assistance to go to college. yes, he put in the work to succeed, but creating those opportunities for anyone to fulfill their individual potential is something we do as organizations. we want to tell that story as well. we train people not to tell individual stories in the same way, but rather to talk about successes in context of the work that they do. we don’t like to talk about “vulnerable” populations; no one describes themselves as vulnerable. we like to talk about issues that surround a vulnerability—a young person with an addicted parent, for example. we have seen that the changes in framing cause positive reactions in the public and we are seeing success in fundraising campaigns. why is the reframing initiative important for the sector and society? the initiative is an opportunity for human services organizations to explain their work to the public so that they understand the critical nature and wide range of work being done. for those that adopt the frame, it’s an important part of their continued viability and opportunity to sustain themselves through funding, human capital, or public recognition of work that they do. today, there is a lot of casting of blame, and separation of “the other” instead of building stronger communities. if we can’t successfully navigate that gap, it’ll have a detrimental effect on our ability to continue to provide the services and preventive work, and shape policies that build strong communities. the reframed narrative emphasizes the broader community and the piece that we all play in that community as opposed to isolating individuals in that community. we get people thinking about how it’s not just “someone else’s” problem, but it also influences their own lives. they can be part of a community that is better off, where everyone is treated better and can be successful. how can individuals be involved in the initiative? explore the research and the toolkits online. then, the idea is to think about it as you’re communicating. think: am i talking about human potential and building well being, and not calling anybody vulnerable? the goal is for each of us to use different language. i’ve seen it work, and it’s pretty powerful. framing is a process of making choices about what to emphasize—and what to leave unsaid. instead of this…. we’re trying this…. individual benefit: helping vulnerable populations. collective benefit: fostering the human potential available to us. ladder metaphors: helping people climb out of poverty. construction metaphor: human services build well being. the triage theme: direct services address urgent needs. strands of human services theme: advocacy, planning, research, preventionanddirect services. proving the worthiness of recipients. explaining common human needs. source: national reframing initiative, national human services assembly. [button color=”black” size=”normal” alignment=”none” rel=”follow” openin=”newwindow” url=”nassembly.org/national_reframing_initiative”]see more atnational human services assembly.[/button]

Listen to this article

This is a powerful article. How can I get permission to print and share it with some local non-profits?

Hi, Sally!

Thank you! We can email you over a PDF version of the story.