The Double Punches Boxing Club promotes confidence and character.

By Maria Lopez

Richard Lopez grew up fatherless, without a male role model in the home, which laid the groundwork for a childhood clouded by drug abuse and gang violence.

After several years of struggling to find his way, two people came along and inspired Lopez to change. One was a pastor. The other, a boxing coach.

These two men taught him a life-shaping lesson: In order to be successful, you must develop—physically, mentally and spiritually.

Now founder and director of the Santa Rosa, Calif., Double Punches Boxing Club, Lopez teaches boxing to at-risk youth with that same philosophy. He refers to the children in the program as “treasures.”

“I go into these neighborhoods that few people want to go into because they don’t see anything good that can come out of them,” Lopez said. “But God has showed me that there are leaders, workers and potential there and boxing is the tool that God has given me to reach these treasures. I don’t have much money, but I consider myself a rich man.”

It started in 1991. Lopez, who holds a Level III Coaches License from USA Boxing Inc., hung a punching bag and speed bag in his garage for his own use. Kids from the neighborhood would come by and ask him to show them how to hit the bags. Then, one parent brought his son over and asked if Lopez would train him for The Golden Gloves, an annual amateur boxing tournament.

After that came another student. Then another. Lopez began to see gangs as an emerging problem in the community. Eager to do something, he formed Double Punches Boxing Club, an outlet for youth in Santa Rosa, especially those vulnerable to gang recruitment.

Pretty soon, the small garage could no longer provide adequate space for training. The next year, he moved into a larger garage, then a small building. By 2005, they had outgrown that building. Lopez met then-Captain Fred Rasmussen of The Salvation Army’s Santa Rosa Corps, and Rasmussen saw that The Salvation Army and Double Punches shared a similar mission and vision for reaching the community. A trial partnership followed.

“They really became the darling of the community,” Rasmussen said of Double Punches. “They had an effectiveness for providing a foundation for kids who were headed down the route of delinquency. For us, it was not a difficult marriage. It was a natural fit.”

“They really became the darling of the community,” Rasmussen said of Double Punches. “They had an effectiveness for providing a foundation for kids who were headed down the route of delinquency. For us, it was not a difficult marriage. It was a natural fit.”

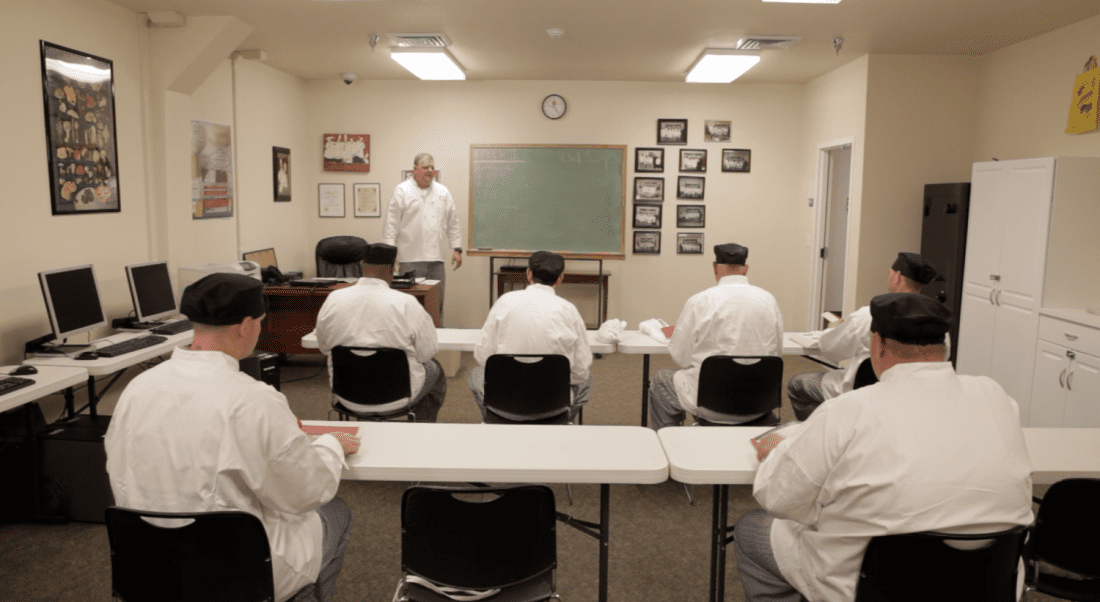

In July 2010, The Salvation Army adopted Double Punches as an official corps program, moving it into a 4,000-square-foot facility at the corps. There, it runs a year-round program for approximately 125 youth ages 10-18 and young adults ages 18-24. Double Punches emphasizes fundamentals and discipline rather than brute force and toughness. Its goal is to improve the confidence and character of young people and re-channel their energy into positive activities.

Participants are asked to make a three-month enrollment commitment, however 70 percent stay longer, according to Double Punches staff. Its After School Books and Boxing Program is $100 per semester with academic incentive discounts of $10-$20 available. This includes picking up the students from four school locations, approximately one hour of homework assistance courtesy of The Salvation Army Tutoring and Mentoring (TAM) program, a snack and 1.5 hours of boxing lessons two to four times per week. It’s open Monday through Thursday from 3-7:30 p.m.

Double Punches has also served as an active member on the Mayor’s Gang Prevention Task Force for the City of Santa Rosa since 2006. The task force is engineered to stop violence and victimization through enforcement and intervention efforts and to redirect young people to services aimed at keeping them out of gangs. Since 2006, the number of total crimes per 100,000 persons per year in Santa Rosa has fallen 21 percent from 3,302 to 2,606. In 2013, Double Punches was added to the Sonoma County Portfolio of Model Upstream Programs—initiatives deemed valuable to the community.

Parents are impressed by the impact of the program. Alicia Alvarenga, aunt and guardian of member Angel Jimenez, called Double Punches an “amazing program.”

“I have seen my child’s outlook on life become happy again,” Alvarenga said. “It has given him an amazing experience that has changed his life and he will always hold close to him.”

While boxing may appear an unorthodox, even ironic way to counter violence, Rasmussen insisted it’s not about “smashing someone in the nose,” but rather building character and good sportsmanship. Social worker Whitney Wright addressed the seeming paradox in her 2006 study, “Keep It in the Ring: Using Boxing in Social Group Work with High-Risk and Offender Youth to Reduce Violence.” In the study, Wright uses examples from boxing groups in New York City and San Francisco that merge boxing training with group discussion.

“For many group members who experience violence or emotional abuse in their communities, home, schools, or from the police, the safest time in their week is at the boxing gym,” she writes. “Training to be a boxer taps their strengths and helps them learn more about themselves, gain confidence and find a way out of violence.”

Brian Munoz joined Double Punches as a sixth grader and stayed in the program through high school. He said getting in shape was just one of the benefits of the program.

“I joined because I wanted to be active as well as work on my self esteem,” Munoz said. “Double Punches not only helped me stay fit and maintain a healthy lifestyle but I also learned discipline, determination, dedication and desire. I learned life lessons that I will never forget and that I will carry with me throughout my life.”

Araceli Sandoval came to Double Punches when she was 14, a period when her home life was anything but stable.

“During that time there was lots of problems at home,” she said. “Without Double Punches I don’t know where I would be. Seriously, from my heart, this was more like a family to me.”