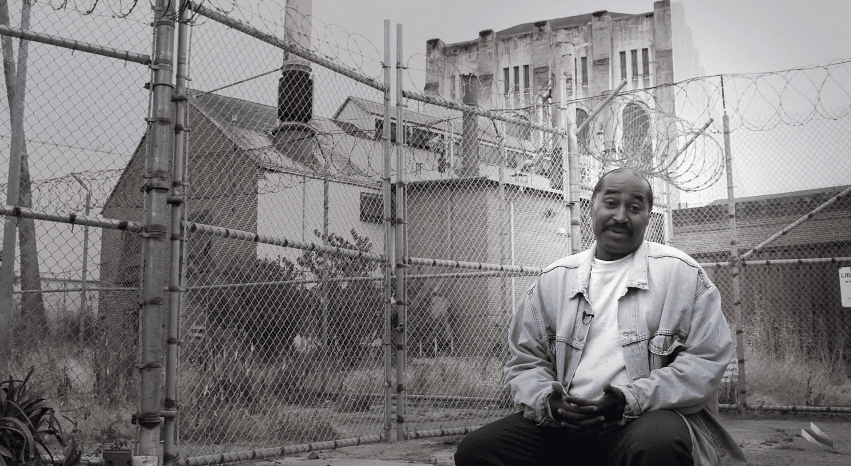

The Last Mile teaches inmates coding and programming in prison so they can put it to use once they’re out.

Inmates in San Quentin State Prison sit just a short trek from the tech giants that occupy Silicon Valley. Yet, inside the walls of the facility, they spend their days coding, programming and developing much like their San Jose counterparts––but without the six-figure salaries.

Venture capitalists Chris Redlitz and Beverly Parenti received an invite a few years ago to conduct a business guest lecture for the inmates at San Quentin. Business as usual, they thought.

But their scheduled half-hour lecture turned into a three-hour dialogue with the inmates on entrepreneurship, technology and future aspirations. Fascinated by the inmates’ potential, Redlitz and Parenti established The Last Mile (TLM) in 2010 as a six-month technology entrepreneurial program (TEP) for incarcerated individuals. TLM tackles California’s soaring recidivism rates by providing inmates training for today’s technologically advanced economy.

The TEP begins during incarceration and continues post-release by facilitating opportunities for paid employment. Through training, students create a business idea that includes a technology component and a social cause. Additionally, selected participants present their five-minute pitches at the annual “Demo Day” to invited guests and fellow inmates. Then after release, TLM uses an extensive personal and professional network to help guide TLM graduates with mentorship and re-entry assistance.

“By the year 2020, it is projected that there will be nearly 1 million unfulfilled computer developer jobs,” Redlitz said. “To me, providing a program for these men just makes sense.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, employment of software developers is projected to grow 22 percent from 2012 to 2022, employment of applications developers is projected to grow 23 percent and employment of systems developers is projected to grow 20 percent.

Conversely, California’s 64 percent recidivism rate is one of the highest in the U.S., according to the U.S. Department of Justice. A Pew Charitable Trusts Survey estimates that reducing recidivism by just 10 percent a year would save Californians around $233 million.

Dr. Lindsay Phillips, assistant professor of psychology at Albright College, studies re-entry and works with with ex-offenders as they return to society. While ex-offenders face many barriers upon release, she said employment is among the most commonly cited.

“Many jobs do background checks so it is incredibly difficult, especially for people with felonies to find employment,” Phillips said. “Obviously there’s a stigma toward people who are formerly incarcerated and sometimes there’s a tendency to not want to give someone a second chance, which is unfortunate because there are a lot of people who return to society and are ready to make changes and who want to be good citizens but because of their record they’re not given a chance.”

Incarceration also creates a gap in employment history on an ex-offender’s resume, so even if a company forgos a background check, the applicant still has to answer for why they were unemployed for however long they were in prison.

According to Phillips, efforts such as TLM to equip inmates with employable skills while they’re still in prison as opposed to once they’re out are key to decreasing recidivism.

“The second they get out they’re faced with so many challenges,” she said. “The more we can do while people are incarcerated to get them prepared for the outside…the better off they’ll be. People need to be building their resources and their networks while they’re incarcerated. The more we can do to help them, it’s going to help our communities be safer, it’s going to help their families, and maybe most importantly, it’s going to help their kids.”

Over the last four years, TLM started four classes and launched Code.7370, a six-month computer programming class that teaches HTML, CSS and JavaScript eight hours a day, four days a week, all without any access to internet connectivity. The curriculum was co-created by TLM and HackReactor, a San Francisco-based software career accelerator. Participants are not required to have prior experience with web development or computer literacy, but are selected based on their ability and motivation to learn the material. Currently, the program provides 18 men with essential skills for the technology-driven marketplace.

Many of the inmates have never used a computer or mobile phone before, let alone studied web development. By introducing students to technology, TLM allows for a smoother transition into the digital age.

“For the record, I’ve never Googled, Skyped, Facebooked, Twittered, scanned, Instagrammed, or even knew what a mobile app was before joining TLM,” said Christopher Schuhmacher, a graduate of TLM’s TEP program and a current student in Code.7370, “Being a part of this group has been a remarkable opportunity for me to catch up on the world of technology that has been passing me by.”

Schuhmacher turned to physical fitness to pull himself out of a drinking and drug addiction that sent his life into a downward spiral. “Becoming incarcerated and realizing the harm that I caused motivated me to stop using and start leading a healthier lifestyle,” said Schuhmacher. He developed the idea for “Fitness Monkey,” a mobile app that allows users to track their fitness and recovery success and reward them for achieving personal milestones. Through Code.7370, he has started building a website for it.

Although the program is only available inside San Quentin State Prison, TLM plans to expand Code.7370 to Folsom Women’s State Prison. While some facilities allow in-prison volunteer education programs, there are relatively few re-entry programs that focus on entrepreneurial and computer skills. The hope is that this pilot program of teaching computer web development without connectivity will expand to prisons across the nation.

“By providing marketable skills to a demographic that needs them, in a market that could benefit from this type of diversity, we can reduce recidivism while simultaneously strengthening our economy,” Redlitz said. “It’s a win-win.”