Listen to this article

Listen to this article

Loading

Play

Pause

Options

0:00

-:--

1x

Playback Speed- 0.5

- 0.6

- 0.7

- 0.8

- 0.9

- 1

- 1.1

- 1.2

- 1.3

- 1.5

- 2

Audio Language

- English

- French

- German

- Italian

- Spanish

Open text

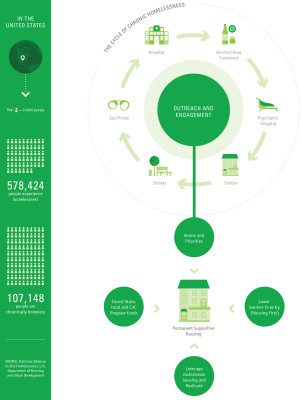

housing first, care second. pathway to housing’s simple yet revolutionary way to help the chronically homeless. gerard thomas gerard thomas served with the u.s. army in the vietnam war, and then lived on the streets of washington, d.c., sleeping on park benches, in alleyways and deep in the woods of rock creek park for 30 years. “i came home from the service with a lot of baggage,” he said. he didn’t realize it at the time, but the weight that he carried was undiagnosed—and consequently untreated—paranoid schizophrenia. he soon became involved in the drug culture of the 1970s and lost his family, his job and most of his friends. eventually, thomas was arrested and entered into a common trap for those struggling with mental illness—cycling prisons, to mental institutions and back to the streets. he might have found treatment in a state psychiatric hospital, but the movement toward deinstitutionalization in the 1960s offered the hope of a better system of care at home. but without a home, many people lacked adequate care. the national alliance to end homelessness found on a single night in january 2014 that 578,424 people in the united states were experiencing homelessness—sleeping outside or in an emergency shelter or transitional housing program. that number includes a subset of individuals with disabling health and behavioral health conditions who experience homelessness for long periods or in repeated episodes over many years—people experiencing chronic homelessness. this number amounts to 107,148 individuals, according to the latest u.s. department of housing and urban development (hud) estimates. deinstitutionalization, which critics say increased chronic homelessness, started when president john f. kennedy signed the community mental health act in 1963 to provide federal funding for community mental health centers as an alternative to state facilities. it aimed to allow patients to live at home and receive treatment locally. then medicare and medicaid passed in 1965 without funding for patient care in mental health institutions. to qualify for funding, states began to push patients out of expensive state mental hospitals and into nursing homes. but the community mental health program, which promised to afford patients independence and consistent mental health care, was never fully funded. without the proper funding or standardized methods of care, many people struggling with mental illness were unable to find permanent housing or maintain the housing that they had. as one consequence, over time the percentage of people with mental illnesses in prisons increased. > infographic by mayra magalhães gerard thomas" width="301" height="400" srcset=" 301w, 771w, 829w" sizes="auto, (max-width: 301px) 100vw, 301px">click to enlarge &>&>infographic by mayra magalhães gerard thomas according to a study by the national alliance for the mentally ill, 64 percent of local jail inmates, 56 percent of state prisoners and 45 percent of federal prisoners have a serious mental illness. people experiencing chronic homelessness cost the public up to $50,000 per person per year through their repeated use of emergency rooms, hospitals, jails, psychiatric centers, detox and other crisis services, according to the u.s. interagency council on homelessness. all of these factors led psychologist dr. sam tsembiris to a simple yet revolutionary way to help the chronically homeless—give them housing. he called this the housing first method and started pathways to housing in new york city to prove that it worked. it did. since then, the method has maintained an 85 to 90 percent housing retention rate, compared to a 40 to 50 percent average success rate among other homeless housing programs. utah was the first state to test the method in 2003, placing 17 chronically homeless individuals in homes. a year later, 14 of them were still in their homes and on the road to recovery; the success led to statewide implementation. in april 2015, state officials announced chronic homelessness was down 91 percent with just 178 people still chronically homeless in utah. the state estimates that housing first has saved its taxpayers $8,000 per formerly homeless person. “there’s a really simple solution to ending chronic homelessness and that is providing people with housing,” said christy respress, executive director of pathways to housing d.c. “often times, we offer people other things first but that’s not what people need; they need housing first. that way, they can actually start to address other things.”. respress said that many housing programs have certain requirements before an individual can be considered housing ready. in contrast, the housing first method teaches that a person is housing ready when he or she asks for housing. respress said this offers a chronically homeless individual an undercurrent of stability that allows him or her to focus on taking charge of their health. “if people could get better while on the street, they would do that,” she said. “no one wants to stay on the street and battle addiction and if they could get better on their own, they would. they were stuck.”. pathways to housing now has programs in d.c., vermont and pennsylvania, and trains other organizations in the housing first method out of its corporate headquarters in new york city. in its own programs, community volunteers identify clients on the street and simply ask what they need. “most people say, ‘i just want to be normal. i just want a normal apartment and to be on my own,’” respress said. do good partner with pathways to housing to bring the housing first model to your community. visit for more information. visit volunteer.usawest.org or volunteermatch.org to find opportunties to volunteer at a homeless services organization in your community. find more about the salvation army’s services for veterans. support specialists help those interested in housing find and apply for an apartment. clients hold their own lease, paying for their housing through section 8 vouchers and disability income. an assertive treatment team—including a psychiatrist, addiction specialist, social worker, nurse and a peer who has been through the process—then offers additional, voluntary support. by uncoupling housing and support services, respress said clients know that their homes will not be taken away if they stumble on the road to healthy living. “it is revolutionary and it really, truly is the answer to ending homelessness,” respress said. “we have really led the charge in changing the system to say every person deserves housing and respect and an ability to recover.”. tsembiris’ housing first idea is helping to fulfill the promise of deinstitutionalization: community mental health centers with permanent supportive housing. this was just what gerard thomas needed. “they saved me,” thomas said. “somebody who had been homeless for a long time and they provided all of these other wraparound services to help me become the person that i am.”. he now works as a certified peer health specialist, helping other formerly homeless veterans to live healthy and meaningful lives. “hope is the key to everything,” he said. “you’ve gotta have hope.”. but before pathways gave him hope, they gave him housing.

Open context player

Close context player

Plays:-Audio plays count

housing first, care second. pathway to housing’s simple yet revolutionary way to help the chronically homeless. gerard thomas gerard thomas served with the u.s. army in the vietnam war, and then lived on the streets of washington, d.c., sleeping on park benches, in alleyways and deep in the woods of rock creek park for 30 years. “i came home from the service with a lot of baggage,” he said. he didn’t realize it at the time, but the weight that he carried was undiagnosed—and consequently untreated—paranoid schizophrenia. he soon became involved in the drug culture of the 1970s and lost his family, his job and most of his friends. eventually, thomas was arrested and entered into a common trap for those struggling with mental illness—cycling prisons, to mental institutions and back to the streets. he might have found treatment in a state psychiatric hospital, but the movement toward deinstitutionalization in the 1960s offered the hope of a better system of care at home. but without a home, many people lacked adequate care. the national alliance to end homelessness found on a single night in january 2014 that 578,424 people in the united states were experiencing homelessness—sleeping outside or in an emergency shelter or transitional housing program. that number includes a subset of individuals with disabling health and behavioral health conditions who experience homelessness for long periods or in repeated episodes over many years—people experiencing chronic homelessness. this number amounts to 107,148 individuals, according to the latest u.s. department of housing and urban development (hud) estimates. deinstitutionalization, which critics say increased chronic homelessness, started when president john f. kennedy signed the community mental health act in 1963 to provide federal funding for community mental health centers as an alternative to state facilities. it aimed to allow patients to live at home and receive treatment locally. then medicare and medicaid passed in 1965 without funding for patient care in mental health institutions. to qualify for funding, states began to push patients out of expensive state mental hospitals and into nursing homes. but the community mental health program, which promised to afford patients independence and consistent mental health care, was never fully funded. without the proper funding or standardized methods of care, many people struggling with mental illness were unable to find permanent housing or maintain the housing that they had. as one consequence, over time the percentage of people with mental illnesses in prisons increased. > infographic by mayra magalhães gerard thomas" width="301" height="400" srcset=" 301w, 771w, 829w" sizes="auto, (max-width: 301px) 100vw, 301px">click to enlarge &>&>infographic by mayra magalhães gerard thomas according to a study by the national alliance for the mentally ill, 64 percent of local jail inmates, 56 percent of state prisoners and 45 percent of federal prisoners have a serious mental illness. people experiencing chronic homelessness cost the public up to $50,000 per person per year through their repeated use of emergency rooms, hospitals, jails, psychiatric centers, detox and other crisis services, according to the u.s. interagency council on homelessness. all of these factors led psychologist dr. sam tsembiris to a simple yet revolutionary way to help the chronically homeless—give them housing. he called this the housing first method and started pathways to housing in new york city to prove that it worked. it did. since then, the method has maintained an 85 to 90 percent housing retention rate, compared to a 40 to 50 percent average success rate among other homeless housing programs. utah was the first state to test the method in 2003, placing 17 chronically homeless individuals in homes. a year later, 14 of them were still in their homes and on the road to recovery; the success led to statewide implementation. in april 2015, state officials announced chronic homelessness was down 91 percent with just 178 people still chronically homeless in utah. the state estimates that housing first has saved its taxpayers $8,000 per formerly homeless person. “there’s a really simple solution to ending chronic homelessness and that is providing people with housing,” said christy respress, executive director of pathways to housing d.c. “often times, we offer people other things first but that’s not what people need; they need housing first. that way, they can actually start to address other things.”. respress said that many housing programs have certain requirements before an individual can be considered housing ready. in contrast, the housing first method teaches that a person is housing ready when he or she asks for housing. respress said this offers a chronically homeless individual an undercurrent of stability that allows him or her to focus on taking charge of their health. “if people could get better while on the street, they would do that,” she said. “no one wants to stay on the street and battle addiction and if they could get better on their own, they would. they were stuck.”. pathways to housing now has programs in d.c., vermont and pennsylvania, and trains other organizations in the housing first method out of its corporate headquarters in new york city. in its own programs, community volunteers identify clients on the street and simply ask what they need. “most people say, ‘i just want to be normal. i just want a normal apartment and to be on my own,’” respress said. do good partner with pathways to housing to bring the housing first model to your community. visit for more information. visit volunteer.usawest.org or volunteermatch.org to find opportunties to volunteer at a homeless services organization in your community. find more about the salvation army’s services for veterans. support specialists help those interested in housing find and apply for an apartment. clients hold their own lease, paying for their housing through section 8 vouchers and disability income. an assertive treatment team—including a psychiatrist, addiction specialist, social worker, nurse and a peer who has been through the process—then offers additional, voluntary support. by uncoupling housing and support services, respress said clients know that their homes will not be taken away if they stumble on the road to healthy living. “it is revolutionary and it really, truly is the answer to ending homelessness,” respress said. “we have really led the charge in changing the system to say every person deserves housing and respect and an ability to recover.”. tsembiris’ housing first idea is helping to fulfill the promise of deinstitutionalization: community mental health centers with permanent supportive housing. this was just what gerard thomas needed. “they saved me,” thomas said. “somebody who had been homeless for a long time and they provided all of these other wraparound services to help me become the person that i am.”. he now works as a certified peer health specialist, helping other formerly homeless veterans to live healthy and meaningful lives. “hope is the key to everything,” he said. “you’ve gotta have hope.”. but before pathways gave him hope, they gave him housing.

Listen to this article