How the advisory board came to be

By Edward McKinley, Dr. –

Igor Sikorsky, the inventor of the helicopter, once declared that the bumblebee cannot fly, according to the laws of aerodynamics. Its wings cannot support its weight in flight. In ignorance of this, the bumblebee flies. Similarly, The Salvation Army cannot fly on its own wings. Enter the advisory board.

The Salvation Army provided care to 30 million people in the United States in 2013, which required an income of $4.3 billion. Yet, member contributions, government grants, fees for service, kettles and all forms of indirect support, total a fraction of what the Army needs. Without faithful advisory boards, the Army as we know it would not be.

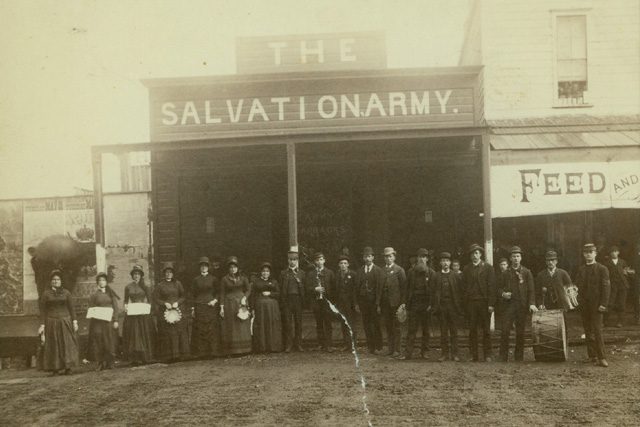

The Salvation Army expanded to the U.S. in March 1880. Led by an eccentric zealot named George Railton, the pioneer party was not a promising group. Five of the six ladies soon quit. Within six years though, the Army grew to 286 locations. By 1890—10 years after the Army’s arrival—one of the country’s most respected theologians declared The Salvation Army to be the most important spiritual development in American history. The Army now serves in all of the country’s roughly 43,000 zip codes.

What role has the advisory board played in the drama?

A ‘new axiom’

In 1898 the national commander said, “The uniformity of the plan, the unity of action, and the universality of application of the simple principles of the Army have accomplished results which would otherwise have been impossible.”

The national commander was not alone in noticing that the Army had accomplished much in little time with few people. This drew favorable attention from men and women of wealth and influence. Principles of modern management were emerging, with emphasis on “raising the rate of results achieved to the efforts expended.” An advocate of modern business techniques declared in 1903 that there was a new “‘axiom of social geometry’—that the shortest distance between two points if something needs doing is to do it—the more plainly, directly and honestly, the better.”

According to a San Francisco newspaper, what appealed to such people was not the Army’s style but its results. Business leaders believed that the “practical value which The Salvation Army does for the fallen, the suffering and the needy [was] beneficial to those needing these ministrations and therefore to society at large.” A business supporter in Washington D.C. wrote in 1896 that the Army’s military discipline was the whole reason for its great success.

The Army’s leaders then recognized that its growing social welfare programs could no longer be financed by ordinary religious activities alone. The wave of endorsements and encouraging newspaper comment, so different from the ridicule of the early days, presented Army leaders with a rare opportunity.

Auxiliary League born

Army leaders acknowledged that it would be contrary to God’s will to ignore offers of practical help from generous and friendly outsiders.

In 1887, then-National Commander Ballington Booth invited support from a small number of people who believed in the Army’s good work. He called this group the “Auxiliary League.” The officer placed in charge of the new venture was Edith Marshall, a 22-year-old girl who described the league as “persons who, while not perhaps endorsing and approving every method used by the Army, are sufficiently in sympathy with [its] great work.”

By 1896, the Auxiliary League had 6,000 members, each of whom paid $5 a year in dues and wore an Army lapel badge. The league was a promising start but struggled to spread beyond New York and a few nearby cities. It faded with Ballington’s departure.

The great turning point in the development of the advisory board system came with The Salvation Army’s services to American troops in World War I. Doughnuts and coffee provided by young ladies practically on the front lines made The Salvation Army immensely popular. Soldiers praised the “brave lassies.” Popular songs were written about the Army. A government freighter was even named for the “Salvation Army Lass.”

After the war, then-National Commander Evangeline Booth proclaimed that the Army’s success in its service to American service personnel was due entirely to its military approach. “We are trained to give no quarter to the enemy.” When the need arose in 1917, The Salvation Army was ready for fast action, keeping a clear vision of doing the most with the least.

Near the end of the war, the general commanding the U.S. Third Division in France predicted that “when peace returns The Salvation Army is going to receive such a boom from the boys who encountered it in the trenches.” After the Armistice in 1918, John Wanamaker, department store magnate, announced, “something should be done to perpetuate The Salvation Army and its work” at home.

Unwavering contribution

The Army’s popularity with the returning soldiers prompted the rapid extension of organizations of supporters among local business and civic leaders in every sizable town in the country. The “advisory board system” began in January 1920. Within one year, advisory boards operated in 1,500 counties in 24 states. The Army boards were often supported by “Community Chest” (later the United Way), which also multiplied rapidly in the 1920s. By 1925, an Army leader announced “an army of not less than 20,000 business and professional men” linked to The Salvation Army” as advisory board members.

Through the decades, the support of the advisory boards became indispensable. Look no further than the events of December 2014 in Henderson, Ky.

When the corps officers, Majors Jerry and Jean Mullins, learned in November that their son in another state was mortally ill, the board members took over the entire corps program during the busy Christmas season so the Mullins could spend all remaining time with their son.

In the decades since the board system emerged, the Army has coordinated local efforts with national public relations campaigns. An official manual with a list of national guidelines for advisory boards first printed in 1957. The process culminated in the creation of the National Advisory Council in 1976, the immediate predecessor of the current National Advisory Board.

The contributions of advisory boards on every level over the past 90 years comprise the lifeblood of The Salvation Army in the United States.

Find resources for advisory boards at mysaboard.org.