‘O Boundless Salvation’ unites WWII enemies

By Jacques Rouffet, Major –

Originally from the south of Germany, Günter had the figure of an athlete—blond hair and blue eyes, yet genteel and remarkably humble. While a student of Tübingen University in Germany, I was invited to a meal at his house. I’d been told to ask about his testimony.

I didn’t need to ask Günter, who was now a soldier of The Salvation Army. At the end of our meal he placed a small metal box on the table from which he extracted some documents and old, yellowing pictures. On the white tablecloth, laid before my eyes, was Günter’s childhood, his youth, his life.

Born into Bavarian nobility, Günter received the strict education of young men of his rank. As I attentively listened to him,my eyes stopped on a picture that filled me with fear—there, astride a black horse, Günter was wearing with pride and arrogance the uniform of an SS officer.

“Yes, that is me,” he said. “I was young and stupid, but from childhood I was taught that Germany would conquer Europe and that as a young intellectual I was part of this elite.” I believed him. “My family, friends and teachers told me the same thing,” he said. “How could I refuse to enroll?”

So how, I asked, did he come to be a soldier of The Salvation Army?

As a 20-year old SS officer, he was sent to Strasburg in 1943 with the job of gathering and burning all the books that did not reflect the Nazi ideology and disbanding any organizations and churches opposed to the Reich. “At the time The Salvation Army was considered to be a dangerous propaganda machine for the enemy,” he said. “Even though we knew the Salvationists were doing good, especially among the poor, I had been given a job to do.

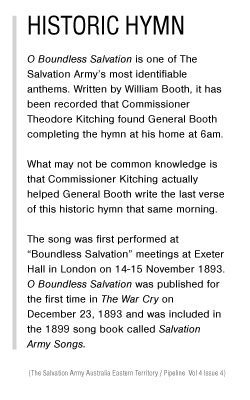

“One November day, after my men had ransacked The Salvation Army hall, I entered the building where flags, Christian newspapers and flyers had been burnt. I found some of their hymn books in French and German. The German book also had music, so being a musician I sat at the dust- and ash-covered piano and started to play the melody of the first hymn I turned to.

O boundless salvation! Deep ocean of love…

O boundless salvation! Deep ocean of love…

“I stopped playing and thought about the place I was in—broken chairs, smashed windows and swastikas painted on the walls. A crest of The Salvation Army was smashed into pieces, cutlery and plates were scattered on the floor. ‘Where is their God?’ I thought, smirking. I put the hymn books in a box and took them with me to burn.

Called back to Berlin the same day, Günter forgot about the hymn books until the following day.

“Fearful of being accused of being part of this ‘strange’ Army, I resolved to throw them in a fire located at the bottom of Landerberg Allee. As I hurried to get to the huge fire I went past a dilapidated evangelical church. To my great surprise, I heard the same melody I had been playing.”

O boundless salvation! Deep ocean of love…

“I went in. Seven French prisoners of war (POW) were laboriously singing ‘O Boundless Salvation’ and needless to say they were absolutely petrified to see me among them! They were gaunt and filthy—a pitiful sight as they played the melody by candlelight on an awfully out of tune piano. They were stumbling over the words of a hymn tune that they couldn’t fully recall.

“’Nicht! No, not like that,’ I said to the pianist in my bad French. I vigorously pushed him aside and started to play the tune. ‘Go on! Sing! Books, in the box there.’ They obediently took books and sheepishly began to sing the Founder’s song, which they finished confidently.

“’Stille Nacht, bitte,’ one of them asked. It was Christmas, so what could I do? I started to play the melody and they sang along in their language and I in mine. As we sang, I pictured my family around the Christmas tree, sharing meals and gifts as a sign of peace and love. As I listened to these French prisoners—my enemies—singing I had the sudden realization that the unity Germany sought to create in Europe by force, had already been won by Christ through his selfless love and sacrifice.

“Unable to contain my emotions and feeling the love of God invading me, I rushed from the church with a heavy heart and tear-filled eyes, taking with me the Salvationist hymn book.”

As we sat at the table, Günter filled with barely controllable emotion. “Here it is,” he said. “See the stamp here: “This book belongs to Strasburg Salvation Army.”

“Since leaving that church I hated my life, uniform and political party,” he said. “With the help of trusted friends I found refuge in Switzerland, where I stayed until the end of the war, went to church and discovered the Bible. Once back in Germany, I settled in Tailfingen and joined The Salvation Army.”

_______________________________

I had forgotten this extraordinary conversation by the time I entered the training college in London in 1972. Two years later I married Yvonne Chislett and as lieutenants we were appointed to Montparnasse, a small corps in the middle of a Parisian quarter.

One day, one of my sergeants asked me to visit her brother Jean, a soldier of the corps who was unable to worship regularly. Jean was bedridden, and struggling to know what to say I talked about the weather. But after a short while Jean told me his testimony.

“I’ve been a Salvationist all my life,” he said. “There was a time when I thought I’d lose my faith but, strangely, that time proved to be a blessing.

“In 1943, when a soldier in the French Army, I was made a POW and was deported to Berlin where the citizens had pity on us and treated us well. But it wasn’t the same with the SS, who didn’t hesitate to beat us up. While living in a squalid POW camp, a chaplain said he’d met prisoners from my own church and would be delighted to introduce them to me. It was reassuring to meet fellow Salvationists in the middle of this hell, but we kept our meetings secret because The Salvation Army had been banned by the authorities.

“Just before Christmas we were particularly discouraged and demoralized. There was no news from France and spending Christmas far from our families was tough. My friend Paul, a musician, had found an abandoned church on a large street that we didn’t know the name of. ‘The hall is in good condition,’ Paul assured us. ‘There’s even a piano. We could go tonight because the authorities are busy burning books.’

“When we arrived at the church there was not much left, but fortunately it wasn’t raining because we could see the stars through the roof! There were no doors and no electricity. It was so cold that we weren’t surprised that people were singing and dancing to the heat of the book fire on Alexanderplatz. Paul had a candle with him, but without any music he wasn’t very good on the piano.

“We tried to play some well-known hymns to lift our spirits. We played Christmas carols too, but in this dark and sinister place our hearts weren’t in it. Antoine suggested that as we were Salvationists singing the Founder’s song would encourage us, but after the first verse we were only able to hum the second. ‘Lord,’ I cried, ‘we’re losing faith. Give us the strength to sing for you.’ So we tried again. Paul played as best as he could and we sang.”

O boundless salvation! Deep ocean of love…

“Just at that moment a young SS officer entered the hall. We froze in fear when we recognized the black uniform and cap featuring a skull. He looked at us with disdain; he could see we were only insignificant French soldiers—lost, miserable and stinky. I thought this was the end for us, but instead he threw a box on a table and took a book out if it. He pushed Paul off the piano stool and started to play the music—the first bars of the Founder’s song. We were stunned and didn’t dare sing.

“‘Go on!,’ he said. ‘Go on, sing!’ He pointed to the box. Incredible! It was filled with Salvation Army song books in French and German. The first page was stamped: ‘This book belongs to Strasburg Salvation Army.’ We each took a book and tremulously started to sing.

“Paul courageously suggested to the SS man: ‘Stille Nacht, bitte!’ We sang ‘Silent Night’ at the top of our voices, but without warning the SS officer stopped in the middle of a verse and hurriedly left the church, taking the hymn book with him. We never saw him again but we also never forgot that moment when God revealed himself to us in this most unexpected way.”

Jean reached into his bedside cabinet where he took out an old Salvation Army song book. “Look Lieutenant, I kept the one I picked up.” On the first, faded page it read: “This book belongs to Strasburg Salvation Army.”

Jean died just a few weeks later and I lead his funeral. Shortly before the service the undertaker approached me to share his embarrassment. “The family has put one of your hymn books close to Jean’s heart,” he said, “but it belongs to The Salvation Army in Strasburg.”

I replied with a smile, “I know. He’ll take it with him to Heaven.”

Excerpt reproduced with permission from The Officer, January-February 2014.