Listen to this article

Listen to this article

Loading

Play

Pause

Options

0:00

-:--

1x

Playback Speed- 0.5

- 0.6

- 0.7

- 0.8

- 0.9

- 1

- 1.1

- 1.2

- 1.3

- 1.5

- 2

Audio Language

- English

- French

- German

- Italian

- Spanish

Open text

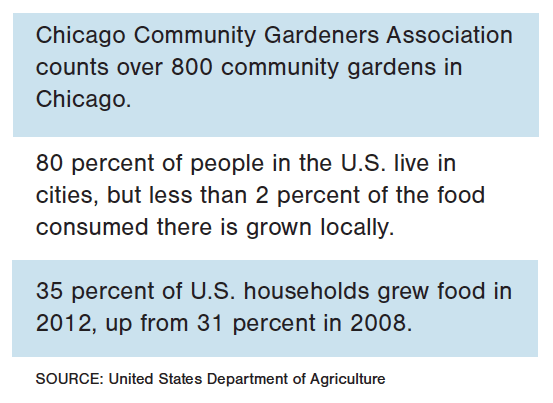

taking root. beatrice jasper with lt. kelly hughes after launching the salvation army’s balcony garden at the red shield corps community center in englewood how gardens are helping some of chicago’s hardest hit areas move toward self-sufficiency. by jared mckiernan –. beatrice jasper is something of a fixture in chicago’s englewood neighborhood. she’s lived there over 50 years, through its boon, its plight and its move toward gentrification. she remembers a brighter englewood. “a lot of the people in our community have been here a long time, like myself,” jasper said. “and so they’ve seen englewood at its best, with the grocery stores and the retail entities.”. that something as simple as a grocery store signifies more prosperous times illustrates just how far the city’s economy has fallen. nearly 23 percent of chicago’s population lives below the poverty line, and only six of the department of labor’s 51 designated large metropolitan areas had higher unemployment rates in february 2015. the american legislative exchange council ranks illinois’ overall economic performance 47th out of 50 u.s. states, and it’s rate of job growth trails 47 other states. yet for all of the issues plaguing chicago, its dearth of affordable, nutritious food—and yes, grocery stores—ranks among the most pressing. when the united states department of agriculture (usda) designated parts of englewood and many neighborhoods of chicago “food deserts,” jasper began working to supply the community with low-cost fruits and vegetables, and to involve as many growers as possible to secure a better future for the city. children prepare a plant bed for seedlings at the chicago ray and joan kroc corps community center for the past five years, jasper has chaired greening the environment through gardening, a nonprofit focused on educating the public on the benefits of gardening. she is involved with roughly a dozen local gardens, and sees them as a way to lower poverty. “growing your own food means that you are able to have some control,” jasper said she regularly tells her neighbors. “you can maintain a food supply that’s right outside your door.”. she had one such conversation with lt. nikki hughes, corps officer at the salvation army adele and robert stern red shield corps community center in englewood. its own limited resources were exacerbated when a city food pantry next door recently closed. “all of their clients then came here,” hughes said. “we never have food that goes bad because we don’t keep it long enough.”. hughes began brainstorming ways to meet the increased need. lacking outdoor space, she researched alternatives and came across milk crate gardening. hughes called on jasper, who introduced the method to seniors from the corps’ drop-in program, and the project took off. the corps added rain barrels and funded the soil and gardening tools, while the roughly 20 seniors secured donations for seeds and seedlings. within a few months, the third-floor balcony garden yielded produce from tomatoes, to lavender, cucumbers and kale. for now, the produce is primarily used for meals at the senior drop-in program, but hughes said she plans to expand the program to benefit more of the community. “it’s not just that more food is needed,” hughes said. “it’s that real food is needed.”. she and jasper acknowledge that the produce benefits more than the individual grower. a study in the journal of nutrition education and behavior showed that adults in flint, mich., who either lived with someone who participated in community gardens, or who participated in one themselves consumed fruits and vegetables 1.4 more times per day, and were 3.5 times more likely to have five fruits and vegetables a day, than those who did not participate. jasper intends the gardens to change the status quo for children in illinois, which has one of the highest rates of childhood obesity for kids ages 10 to 17, according to the trust for america’s health and the robert wood johnson foundation. “to watch them learn some patience with being able to put the seed in the ground and watching it grow and have harvest time come around and watching their amazement,” she said. “even some adults, who’ve never grown their own food in their own lifetime are amazed to finally see a tomato on the vine. to pull up a bunch of carrots at the same time or sweet potatoes; to have children ask their mom, ‘let’s go to the garden and not the grocery store.’ that is so interesting for them.”. the city’s food deserts have drawn attention from policymakers, including chicago mayor rahm emanuel who vowed to eliminate their existence in the city after stepping into office in 2011. he passed a city ordinance softening restrictions on food sales of urban agriculture operations, converted several chicago transit authority buses into “fresh moves” that drive around selling fruits and vegetables, and helped start five new farmer’s markets. emanuel unveiled plans last summer to establish englewood’s first whole foods market in 2016. “i am completely committed to ensuring that all chicagoans have access to fresh, quality and affordable food in their neighborhoods,” he said in a statement following the announcement. yet, jasper does not see the upscale grocer as a step forward for the community with a declining population and a median household income under $20,000. tomatoes on the vine at the east chicago corps’ community garden. “the community itself is intelligent enough to know that whole foods is not englewood’s answer to the food desert,” she said. “having whole food is still like not having a grocery store for the people who live over here.”. jasper said gardening offers a more feasible and affordable approach to food deserts, and offers the additional benefit of limiting violence. chicago professors frances kuo and william sullivan compared crime rates among 98 apartment buildings in a public housing project and found buildings with high levels of vegetation experienced 52 percent fewer crimes than buildings with minimal vegetation. while the latter did not examine the effects of community gardens, specifically, on crime rates, los-angeles-based community gardener ron finley thinks it’s reasonable to extrapolate the findings. “it’s going to affect your mind—greens and fresh air and the hummingbirds and the dragonflies,” finley said. “gardens change people, dude. and they build communities. if people see beauty, they’re more inclined to keep it or to replicate it.”. the chicago community has a rich history of community gardens, dating back to wartime efforts in the early 1940s when food was in short supply in cities across the u.s. as resources were spent on moving troops and equipment for world war ii, with little surplus for fresh produce. chicago residents planted upward of 500 community gardens, plus 75,000 home gardens, according to university of chicago research. during the summer of 1943, these victory gardens produced roughly 55,000 pounds of food. today’s chicago is bigger with more commerce, but the food shortage persists. yet community gardens are sprouting again––the chicago community gardeners association counts over 800 in the city. in east chicago, technically indiana, access to fresh food is a little easier to come by, yet poverty is no less prevalent. once home to a burgeoning steel mill industry, the city now faces a 36 percent poverty rate. this much is evident at the salvation army’s east chicago corps and community center, which serves lunch to as many as 150 people each day. after multiple denials for a community garden grant from foundations of east chicago, the corps looked into many of the benefits jasper touts. “ok, so you’re going to beautify the city; so what? then, you start talking about lowering crime, and you start talking about seniors, and empowering people, that’s a whole different subject,” said rosemary salazar, corps administrative coordinator. with that evidence, the corps secured funding and launched its community gardening program last summer in partnership with foundations of east chicago, purdue university extension center and the home depot. the initiative subsequently spawned both a veterans and senior gardening program, and all of the produce grown is used for meals in the corps’ feeding program. salazar hopes to hold a farmer’s market this year and encourages participants to apply the new knowledge in their own backyards. grower elida ochoa is doing just that. “there are so many recalls on spinach, on cabbages, on tomatoes,” she said. “i always tease my friends, i say, ‘i haven’t had a recall on any of my vegetables yet.’ there’s nothing better than to produce something that your family can eat…if i don’t do it, how am i going to share it with the next generation?”. other locations in the chicago metropolitan division have experimented with community gardening. major darlene harvey, corps officer at the chicago ray and joan kroc corps community center, said the center has partnered with a local school to help educate children on the potentials of growing your own food. the blue island corps runs a rooftop garden, utilizing 30 hydroponic towers equivalent to up to 10 acres of conventional farmland. the vegetables grown are used in the corps’ senior lunch program. regardless of the food produced or crime rates lowered, jasper believes that community gardens should not be mistaken for a panacea to poverty, but said they can provide a notable boost as part of an integrated food system, particularly in urban areas. “community gardening is not an answer—a complete answer,” jasper said. “but, it is something that can certainly make an impact.”.

Open context player

Close context player

Plays:-Audio plays count

taking root. beatrice jasper with lt. kelly hughes after launching the salvation army’s balcony garden at the red shield corps community center in englewood how gardens are helping some of chicago’s hardest hit areas move toward self-sufficiency. by jared mckiernan –. beatrice jasper is something of a fixture in chicago’s englewood neighborhood. she’s lived there over 50 years, through its boon, its plight and its move toward gentrification. she remembers a brighter englewood. “a lot of the people in our community have been here a long time, like myself,” jasper said. “and so they’ve seen englewood at its best, with the grocery stores and the retail entities.”. that something as simple as a grocery store signifies more prosperous times illustrates just how far the city’s economy has fallen. nearly 23 percent of chicago’s population lives below the poverty line, and only six of the department of labor’s 51 designated large metropolitan areas had higher unemployment rates in february 2015. the american legislative exchange council ranks illinois’ overall economic performance 47th out of 50 u.s. states, and it’s rate of job growth trails 47 other states. yet for all of the issues plaguing chicago, its dearth of affordable, nutritious food—and yes, grocery stores—ranks among the most pressing. when the united states department of agriculture (usda) designated parts of englewood and many neighborhoods of chicago “food deserts,” jasper began working to supply the community with low-cost fruits and vegetables, and to involve as many growers as possible to secure a better future for the city. children prepare a plant bed for seedlings at the chicago ray and joan kroc corps community center for the past five years, jasper has chaired greening the environment through gardening, a nonprofit focused on educating the public on the benefits of gardening. she is involved with roughly a dozen local gardens, and sees them as a way to lower poverty. “growing your own food means that you are able to have some control,” jasper said she regularly tells her neighbors. “you can maintain a food supply that’s right outside your door.”. she had one such conversation with lt. nikki hughes, corps officer at the salvation army adele and robert stern red shield corps community center in englewood. its own limited resources were exacerbated when a city food pantry next door recently closed. “all of their clients then came here,” hughes said. “we never have food that goes bad because we don’t keep it long enough.”. hughes began brainstorming ways to meet the increased need. lacking outdoor space, she researched alternatives and came across milk crate gardening. hughes called on jasper, who introduced the method to seniors from the corps’ drop-in program, and the project took off. the corps added rain barrels and funded the soil and gardening tools, while the roughly 20 seniors secured donations for seeds and seedlings. within a few months, the third-floor balcony garden yielded produce from tomatoes, to lavender, cucumbers and kale. for now, the produce is primarily used for meals at the senior drop-in program, but hughes said she plans to expand the program to benefit more of the community. “it’s not just that more food is needed,” hughes said. “it’s that real food is needed.”. she and jasper acknowledge that the produce benefits more than the individual grower. a study in the journal of nutrition education and behavior showed that adults in flint, mich., who either lived with someone who participated in community gardens, or who participated in one themselves consumed fruits and vegetables 1.4 more times per day, and were 3.5 times more likely to have five fruits and vegetables a day, than those who did not participate. jasper intends the gardens to change the status quo for children in illinois, which has one of the highest rates of childhood obesity for kids ages 10 to 17, according to the trust for america’s health and the robert wood johnson foundation. “to watch them learn some patience with being able to put the seed in the ground and watching it grow and have harvest time come around and watching their amazement,” she said. “even some adults, who’ve never grown their own food in their own lifetime are amazed to finally see a tomato on the vine. to pull up a bunch of carrots at the same time or sweet potatoes; to have children ask their mom, ‘let’s go to the garden and not the grocery store.’ that is so interesting for them.”. the city’s food deserts have drawn attention from policymakers, including chicago mayor rahm emanuel who vowed to eliminate their existence in the city after stepping into office in 2011. he passed a city ordinance softening restrictions on food sales of urban agriculture operations, converted several chicago transit authority buses into “fresh moves” that drive around selling fruits and vegetables, and helped start five new farmer’s markets. emanuel unveiled plans last summer to establish englewood’s first whole foods market in 2016. “i am completely committed to ensuring that all chicagoans have access to fresh, quality and affordable food in their neighborhoods,” he said in a statement following the announcement. yet, jasper does not see the upscale grocer as a step forward for the community with a declining population and a median household income under $20,000. tomatoes on the vine at the east chicago corps’ community garden. “the community itself is intelligent enough to know that whole foods is not englewood’s answer to the food desert,” she said. “having whole food is still like not having a grocery store for the people who live over here.”. jasper said gardening offers a more feasible and affordable approach to food deserts, and offers the additional benefit of limiting violence. chicago professors frances kuo and william sullivan compared crime rates among 98 apartment buildings in a public housing project and found buildings with high levels of vegetation experienced 52 percent fewer crimes than buildings with minimal vegetation. while the latter did not examine the effects of community gardens, specifically, on crime rates, los-angeles-based community gardener ron finley thinks it’s reasonable to extrapolate the findings. “it’s going to affect your mind—greens and fresh air and the hummingbirds and the dragonflies,” finley said. “gardens change people, dude. and they build communities. if people see beauty, they’re more inclined to keep it or to replicate it.”. the chicago community has a rich history of community gardens, dating back to wartime efforts in the early 1940s when food was in short supply in cities across the u.s. as resources were spent on moving troops and equipment for world war ii, with little surplus for fresh produce. chicago residents planted upward of 500 community gardens, plus 75,000 home gardens, according to university of chicago research. during the summer of 1943, these victory gardens produced roughly 55,000 pounds of food. today’s chicago is bigger with more commerce, but the food shortage persists. yet community gardens are sprouting again––the chicago community gardeners association counts over 800 in the city. in east chicago, technically indiana, access to fresh food is a little easier to come by, yet poverty is no less prevalent. once home to a burgeoning steel mill industry, the city now faces a 36 percent poverty rate. this much is evident at the salvation army’s east chicago corps and community center, which serves lunch to as many as 150 people each day. after multiple denials for a community garden grant from foundations of east chicago, the corps looked into many of the benefits jasper touts. “ok, so you’re going to beautify the city; so what? then, you start talking about lowering crime, and you start talking about seniors, and empowering people, that’s a whole different subject,” said rosemary salazar, corps administrative coordinator. with that evidence, the corps secured funding and launched its community gardening program last summer in partnership with foundations of east chicago, purdue university extension center and the home depot. the initiative subsequently spawned both a veterans and senior gardening program, and all of the produce grown is used for meals in the corps’ feeding program. salazar hopes to hold a farmer’s market this year and encourages participants to apply the new knowledge in their own backyards. grower elida ochoa is doing just that. “there are so many recalls on spinach, on cabbages, on tomatoes,” she said. “i always tease my friends, i say, ‘i haven’t had a recall on any of my vegetables yet.’ there’s nothing better than to produce something that your family can eat…if i don’t do it, how am i going to share it with the next generation?”. other locations in the chicago metropolitan division have experimented with community gardening. major darlene harvey, corps officer at the chicago ray and joan kroc corps community center, said the center has partnered with a local school to help educate children on the potentials of growing your own food. the blue island corps runs a rooftop garden, utilizing 30 hydroponic towers equivalent to up to 10 acres of conventional farmland. the vegetables grown are used in the corps’ senior lunch program. regardless of the food produced or crime rates lowered, jasper believes that community gardens should not be mistaken for a panacea to poverty, but said they can provide a notable boost as part of an integrated food system, particularly in urban areas. “community gardening is not an answer—a complete answer,” jasper said. “but, it is something that can certainly make an impact.”.

Listen to this article