The people and process that bring The Salvation Army’s most extensive fundraiser to life

By Jared McKiernan

Patricia Eymann, 66, stands at the kettle every year.

“I had noticed the bell ringers out when I went to the store. I thought, ‘Hey, why don’t I do that?’” she said. “I thought it would be a good thing to do. I called up in sort of a nothing-ventured, nothing-gained mood. The worst they can tell me is no. They told me yes.”

Eymann works at a kettle outside a Vons in Long Beach, Calif. She said she likes to sing and spread holiday cheer. In six years, she has helped to raise more than $13,000.

“When the little kids come, that’s really fun,” she said. “I always say, ‘You don’t have to be a ding-a-ling to be a bell ringer but it helps.’”

Eymann is one of 15,089 individuals who stood at one of 6,776 kettle locations in the Western Territory in 2012, helping The Salvation Army raise money. All of the change—and even the occasional diamond ring or gold tooth—collected stays in the community where it is given. In the following year the money goes toward services from food boxes for families to local inmate care packages.

The concept started in 1891 when Captain Joseph McFee was distraught over the number of people going hungry in San Francisco during the holidays. He resolved to provide 1,000 free Christmas dinners for the poorest individuals, but he needed the funds.

McFee remembered seeing “Simpson’s Pot” as a sailor in Liverpool, England. As the boats came in, passerby tossed in coins to help the poor. So he placed a similar pot at the Oakland Ferry Landing at the foot of Market Street with a sign: “Keep the Pot Boiling.” McFee served that Christmas dinner, and the kettle became a mainstay of the holiday season.

This November will mark the 17th year the campaign is launched in a Red Kettle Kickoff halftime show at the Dallas Cowboys Thanksgiving Day game, but for each community, kettle season preparation begins in July.

First, kettle coordinators work to secure locations in the community. The business and property owner must agree to the kettle being onsite in a memorandum of agreement.

Jennifer Freitas, volunteer service coordinator for the Santa Rosa, Calif., Corps Community Center, will be running the corps’ Red Kettle Campaign for the third year. Freitas said she was scared the first year she was asked to organize the campaign, but she now looks forward to planning it.

“I love the kettle season,” Freitas said. “Everyone thinks I’m nuts. I probably am.” Freitas utilizes a kettle worker base comprised entirely of volunteers. The corps’ advisory board made the decision to use only volunteers three years ago to maximize its net earnings. It has increased its kettle earnings each of the past two years, netting more than $189,000 in 2012. The corps enlisted 400 volunteers in its online database and set a goal of $200,000 for this kettle season.

“[The volunteer model] is working well,” she said.

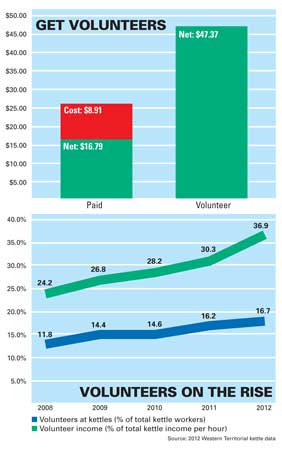

Data from 2012 shows that volunteer kettle workers netted nearly three times as much income ($47 per hour) as paid workers ($17 per hour), according to Tim Schaal, Western Territory director of software development. In 2012, one out of every six kettles was manned by a volunteer, who collectively brought in 37 percent of the West’s kettle income.

This year, a new volunteer management software simplifies registration for volunteers and oversight for coordinators.

“We’re building a whole volunteer army, and the new software system is helping me by capturing everyone’s data and preferences on things like where they want to serve,” said Leslie Baltzell, volunteer coordinator at the Coeur d’Alene Kroc Corps Community Center. The corps has committed to nearly 7,500 hours of bell ringing with a goal to raise $185,000. “The software sends an automatic email thanking the volunteer for signing up, confirming the time and location and providing a video with the basics of how to be a bell ringer.”

To date, Coeur d’Alene volunteers have committed to 51 shifts using the software. Baltzell said she expects many more ahead of Nov. 22, the first day of bell ringing.

“We used to have to call volunteers with a reminder, but now it’s all automatic, which frees my time to continue to recruit volunteers,” she said.

In addition to volunteer bell ringers, The Salvation Army hires seasonal employees to stand at the kettle.

“We find with our kettle workers, a majority of them are actually recipients of our services,” said Lt. Jared Arnold, Tualatin Valley Citadel corps officer. “Commonly, most of our kettle workers hear about us not through our promotions in the newspaper or through Craigslist, but because they receive our services and they want to make a little extra money at the end of the year.”

Jonathan Ludwig, kettle coordinator in Glendale, Calif., said he seeks out individuals in the community looking for seasonal work through The Salvation Army’s community partnerships. “We try to refer out to different organizations we know that have clients who need jobs,” he said. “Word of mouth is probably the biggest thing. And we’re right up the street from an employment agency. We’ve gotten volunteers and paid workers from there.”

On Nov. 6, the Del Oro Division held its 13th kettle preparation day, a mandatory event for each corps officer and anyone involved in the administration of the kettle season.

“This is the ‘rah rah’ before the big battle,” said Major Jeanne Stromberg, Del Oro divisional finance secretary. “It gets people thinking about what it’s all about and one of the messages we give is that it’s not about the money, it’s about the service that can be provided in the name of Christ. The money enables us to reach more people with the gospel and to meet their unique needs.”

The one-day seminar covers everything from how to complete a deposit, to California law in relation to seasonal workers, to best practices and expectations of a bell ringer.

“It helps us behind the scenes and in the public eye,” Stromberg said. “It ensures that everybody is representing The Salvation Army appropriately and everybody is on the same page.”

In January, the corps evaluates the amount raised and determines the funds available for social service programs.

“We try to as much as possible direct it toward programs that are directly community affected, whether that be our back-to-school project, buying school supplies and backpacks, or food and distribution,” Arnold said. “Sometimes that money goes into paying a social service worker, but it’s still going back into the community.”

Bill Miller, administrator of the Minneapolis Harbor Light, organized the most successful Red Kettle Campaign in the country last year, generating $1.4 million in part of downtown Minneapolis. Miller credits the success of the campaign to growing up in a family of Salvationists.

“I’m blessed to have a heritage that taught me how to do this,” said Miller, son of former U.S. national commander, Commissioner Andrew Miller. “But I do my own thing. I’m kind of a maverick in this area.”

Miller has sparked friendships with several Minnesota professional athletes including Adrian Peterson and Kevin Love, which has significantly increased awareness of the campaign. He has also gotten members of every Minnesota professional sports team to join the Minneapolis Harbor Light Advisory Council.

“The [athletes] bring me with them a lot of times to their public speaking [events],” he said. “They get their teammates involved. They get a lot of other people involved.”

Miller stressed the importance of offering paid kettle worker jobs to the community, even if it comes at a financial cost.

“What we’re doing for people by giving them these jobs is just as important as the money we’re raising for our other social service programs,” he said. “It is not just about money. It’s about giving dignity to those who are on the fringes.”

Chaz Watson, executive director of development for the Western Territory, said that serving in communities where no one else will for those who would otherwise go unserved is what makes The Salvation Army unique.

“The Salvation Army treads where others don’t want to,” Watson said. “The kettle campaign reminds the public that people are still hurting and need help and that we’re still serving. It allows us to be visible in the public and rally for a worthy cause, which is the mission of The Salvation Army.”

Back in Long Beach, Eymann can’t see the smiles she creates at the kettle—she is blind—but she takes the laughter as reassurance that she’s making a difference in her community.

“I like it when the people come by,” she said. “I call them visitors. Sometimes, you’re lucky, and they remember you from before.”