Imagine seeing a child in the dumpster behind school looking for food to take home to her family for the weekend.

Or another child walking in one morning who stops at the curb and sits down. Not because he’s lazy, but because he didn’t have the energy to make it in the building.

“Those are things that are etched in our minds, children who are so hungry and filled with such need,” said Captain Tammy Poe who leads The Salvation Army Kauluwela Mission Corps in Hawaii as its Corps Officer. “Teachers told me children would not have food in the home over the weekend and they’d come to school sluggish and hungry.”

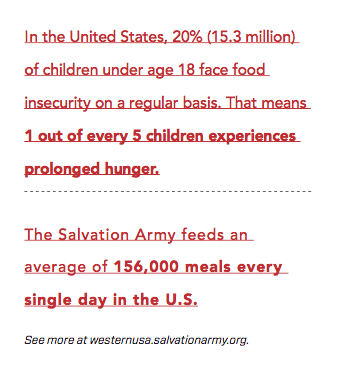

The stories are similar from community to community: teachers and administrators see the same children coming to school hungry each Monday. Sometimes their clothes are disheveled or they’re lethargic. Other times they go to the nurse, complaining of cramps or that their tummies hurt. Often, the root of all that is hunger.

“Come to find out, a lot of the times on Monday morning what you’re having is kids who are starved,” said Lt. James Fleming, Corps Officer in Hemet, California. “We asked, ‘what can we do?’ And the nurse said, ‘feed our kids.’”

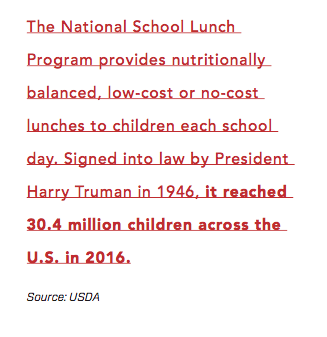

In many of these communities, a majority of the children qualify for free lunch. In Hemet, for instance, 80 percent of families in the school district qualify.

Often these school districts are full of single-parent households, or homes in which only one parent is working. Or maybe mom and dad work on the weekends and they’re not able to be there to prepare meals. Whatever the reason, many of the families struggle to feed their kids when they’re not in school.

“There’s really not too many families that wouldn’t qualify,” said Jhoana Hirasuna, Director of Social Services at the Pasadena Tabernacle Corps—in a city where 60 percent of families qualify for the school district’s free lunch. “We’re quite lenient, we’re not trying to make this difficult for anyone. But we want to make sure our priority is providing meals for the absolutely neediest of families.”

Smaller corps, like the Petersburg Corps in Alaska, particularly feel the financial crunch, said Major Londa Upshaw. The 3,000-person community is dependent on the fishing industry and seasonal work, making lives more difficult in the winter when things shut down.

“It’s a great community, but there’s a lot of families that struggle with lack of work, work availability and income,” Upshaw said. “We see a lot of need with the families to make sure these kids have food to eat over the weekend.”

And so, in communities from Hawaii to Alaska, the Salvation Army Meals (SAM) program aims to provide enough nutritious meals to get the kid through the weekend. Leaders call it one of their favorite programs, adding that it has been well received and supported in the communities.

The food items must be ready-to-eat or require little effort from the child, many of whom are in elementary school. Of course, that makes it more difficult to find healthy items within the allotted budget. Unfortunately, the better quality snack items, such as chicken salad and tuna salad kits, cost significantly more.

“Certainly our goal is to provide as healthy of items as possible,” Hirasuna said. “But when you’re talking a dollar an item versus 20 cents an item, and when you’re talking hundreds of bags packed every week, it certainly makes a difference.”

Still, corps do what they can, selecting items with less sugar and typically only including one sweet item, Hirasuna said. For example, a kid might get two oatmeal packets, a can of ravioli, two packs of fruit snacks, a fruit cup, and a cup of noodles.

Poe learned quickly when moving from California to Hawaii that kids in different regions react differently to the included items. Hawaii residents, she learned, aren’t nearly as big a fan of mac ‘n cheese. But toss in some Spam, and they’re beyond happy.

Food preference is important, Poe said. “If it’s being wasted or thrown away, it’s not helping our situation.”

The logistics of the program are handled differently in each corps. In Hemet, volunteers help pack supplies once a month and then Fleming coordinates with the school district for delivery to 15 schools. Each individual school has a parent liaison who identifies the kids that need the program and distributes applications.

In Pasadena, it’s been more of a challenge to find individuals at each school who are willing to take the program on, Hirasuna said.

“We’ve noticed at some schools the liaison will be very involved, willing to identify families and help them fill out applications,” Hirasuna said. “Others, not so much.”

In Petersburg, Alaska, the operation is even more threadbare. Upshaw is practically a one-woman show, ordering the items, packing the totes herself and delivering them to the local schools. She’ll often grab some of the high school boys to help her carry in the 20 bags.

No matter where it happens, the entire process is kept as confidential as possible.

No matter where it happens, the entire process is kept as confidential as possible.

On Fridays, kids swing by the office at the end of the day and pick up either a white, unmarked plastic bag they can throw in their own bag or an actual backpack with a corresponding number. No identifying information is used.

Most programs are funded through a mix of grants, food drives and community help. In Hemet, teachers and administrators had a food drive of their own, gathering a month’s worth of items for the approximately 150 kids.

Rotary clubs are consistent givers to multiple corps, along with Lions Club and similar groups. Other communities have seen help from the local districts and municipal governments.

“Once a community is made aware of this program and its goal,” Hirasuna said, “people really stand behind it.”

[button color=”black” size=”normal” alignment=”none” rel=”follow” openin=”newwindow” url=”westernusa.salvationarmy.org”]See more about The Salvation Army’s efforts to cure hunger in your neighborhood and give to support the effort at westernusa.salvationarmy.org.[/button]

For the 2018-2019 school year in Grandview Washington, we started the weekend food backpack program in one elementary school. We supplied enough food for 30 children. The backpacks contained a box of cereal or oatmeal, granola bars, fruit snacks, bottle of water, small carton of milk, tuna, Mac n cheese, soup or ravioli, fruit cup, peanut butter. This program went so well that we are now adopting all three elementary schools in Grandview. The counselors are so excited for this program. We will now serve 45 weekend food backpacks to children in need each Friday.