As a child refugee, Liyah Babayan found kindness and a safe haven at the Twin Falls (Idaho) Corps.

In 1989, seven-year-old Liyah Babayan had no idea of how The Salvation Army would one day influence her destiny.

When the Berlin Wall fell late that year, the Western world celebrated the end of the Cold War and subsequent dismantling of the Soviet Union. For the Babayan family and 290 million others living within the crumbling empire’s borders, however, a humanitarian crisis was ramping up.

“My family escaped to Armenia from Azerbaijan that October,” said the Twin Falls, Idaho-based Salvation Army Advisory Board member, entrepreneur and mother to two pre-teens. “We were hunted like animals. The Soviet Union had more than 100 distinct national ethnicities, and with independence movements and nationalists on the rise, it gave rise to widespread ethnic cleansing.”

Babayan’s parents, along with 300,000 Armenians, fled the country after four years—a period that Babayan described as “the scariest of my life. I compare the refugee experience to running out of a burning house, as the only choices we had were to stay and die or run.”

In 1992, the Babayans relocated to Twin Falls. “No one in my family spoke or understood a word of English,” she said. “It was deeply lonely and traumatic for us to be separated from relatives, in a region that lacked diversity and could be unwelcoming to refugees or immigrants.”

Learning to navigate and assimilate in a new country, without access to mental health and other services can have devastating consequences. “I grew up in a household of traumatized, self-medicating adults trapped in the pain cycles of PTSD,” Babayan said. “Refugee parents are left without resources, tools and support to help them cope.”

The effects of war and genocide are no less injurious to children. “It was detrimental to our mental, spiritual, emotional, physical and psychological development,” Babayan said. “It took me many years to understand that PTSD was not my identity or personality, and many more years working with a professional to learn coping skills to live with [PTSD].”

Babayan and her older brother learned English in school, but the programming focused on spoken language, rather than reading and writing. “I was pretty much illiterate all through my public education years,” she said. “By the ages of 10 and 11, we were handling all of our family affairs like doctors appointments, job applications and parent-teacher conferences—which of course were always excellent, according to our translation.”

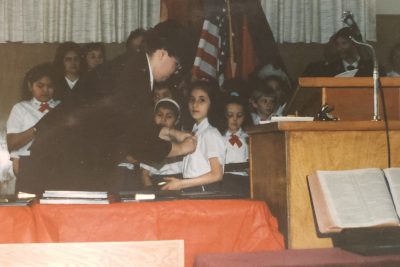

It was then that the family met Lorrie Davis, a Sunday School teacher for The Salvation Army Twin Falls Corps. “Lorrie was foremost my family’s dear, sweet friend,” Babayan said. “She comforted me—a confused, anxious child—and made us feel accepted and valuable by recognizing our intact humanity, even though we were deeply broken, poor, and had nothing to offer back to her.”

Davis recalled getting to know the Babayans, and Liyah in particular, at the Twin Falls Corps. “It took months to be able to communicate with Liyah and her family with words; our communication was one of gestures, smiles and pointing to objects,” Davis said.

“I can still remember Liyah’s eyes analyzing me, deciding if I could be trusted. I could see that she had been through trauma unfathomable to me and was far wiser than children her age, and many adults, and even when they had so little, the family often brought me to their home to share meals and fellowship.”

The Salvation Army also provided Babayan and her brother supplies through its Back-to-School-Backpack program, and eventually employed Babayan’s father as a maintenance man, a position he held for 11 years.

“He recognized the [Salvation Army] logo from the 1988 earthquake that devastated Armenia,” Babayan said. “The Salvation Army was first to respond with humanitarian aid and when we arrived in Idaho, he saw the same logo on a building around the corner from the refugee apartment we were living in.”

The entire family became Salvation Army soldiers in 1993.

“For refugee kids, the organization was more than a church, soup kitchen and after-school hangout,” Babayan said. “It was the first time we felt a safe shelter, friendly interaction and absence of violence. Lorrie’s hugs would make me feel safe.”

Babayan volunteered at The Salvation Army thrift store, served lunch to individuals experiencing homelessness, led the corps’ Creative Ministries team and became a counselor at the Army’s Camp Kuratli—experiences that made her aware of her “personal responsibility” to society, and how that accountability can engender change.

These experiences led Babayan to earn a bachelor’s degree in Political Science and International Studies at Southern Oregon University.

The impact of her early years as a genocide survivor and a refugee sparked her passion for human rights. She chronicled those early years in her memoir, “Liminal.”

In 2007, Babayan opened Ooh La La, a high-end clothing consignment boutique. “We are what we wear,” she said. “If we choose wasteful clothing created under oppressive conditions, we uphold those values. All human beings deserve the same quality of life, and here in the West, especially, we have the power to align our actions and consumption with practices that support human rights.”

Davis is still in touch with Babayan. “It gives me such deep joy to see the young woman Liyah has become,” she said. “I think the Babayans have blessed me far more than I have the opportunity to bless them.”

Babayan also owns Makepeace, an organic potato-based skin care line that donates a bar of soap to those in need for every bar sold. “My work, like my advocacy, is an expression of my spirituality,” she said. “Love for others, our environment, and gratitude for…the life resources we are blessed with.”

In addition to speaking to such organizations as the ACLU, U.S. Foreign Affairs Committee and International Refugee Rescue, Babayan has held public office on various boards and civic committees, including a stint as trustee for the Twin Falls School Board. “The same district I entered not speaking a word of English,” she said.

This fall, Babayan ran for Twin Falls City Council under a grassroots campaign to bring representation of “historically marginalized members of our community to the decision-making process,” and to show her children the importance of being proactive in a free society. “I believe the word ‘American’ is a verb, and as a new American, I regard civic duty with deep gratitude,” she said.

While another candidate won the election, Babayan has no plans to step down from the platform she’s created over the years. Currently in law school, she serves on the advisory board of the ACLU of Idaho as well as on the Twin Falls Salvation Army Advisory Board, assisting the Army with its activities within the community. “It’s the most rewarding full circle,” she said. “Being able to give back to the organization that gave my family so much love.”

Do Good:

- You’ve probably seen the red kettles and thrift stores, and while we’re rightfully well known for both…The Salvation Army is so much more than red kettles and thrift stores. So who are we? What do we do? Where? Right this way for Salvation Army 101.

- How do we treat everyone with love and kindness, as if they were our neighbor? Get the Do Good Family Roadmap and take a 4-week journey for families in how to be a good neighbor. Follow the guide to see what the Bible says about the art of neighboring and take tangible steps together on your printable roadmap to be a caring, helpful, welcoming and supportive neighbor right where you are.

- Find out how former Salvation Army shelter residents are now helping others at the same facility.