As tensions mount with police departments and communities across the country, The Salvation Army helps facilitate positive interactions between them.

By Kristin Marguerite Doidge –

What can a couple of police officers, several youth advisors, and more than 100 youth do together to create positive change? Plenty, according to the Pasadena Police Department and The Salvation Army in Pasadena, California.

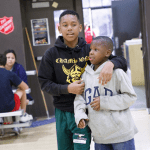

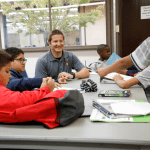

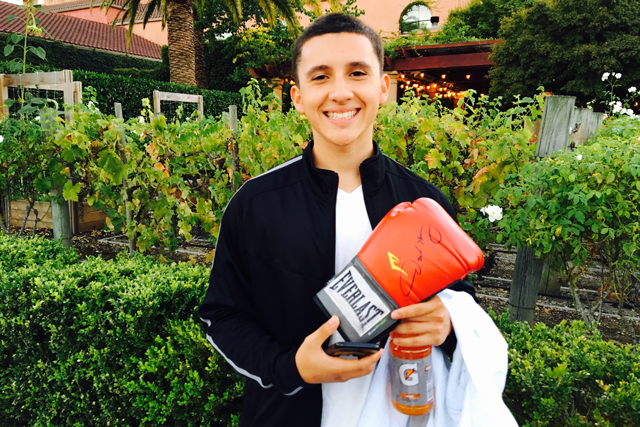

The two organizations have been partnering for 20 years on an initiative called PAL—the Police Activities League—in which students ages 9–17 participate daily in an after-school program year-round with uniformed officers. PAL members receive tutoring, homework assistance, personal development training, and computer training. Other activities include art classes, horseback riding, soccer, boxing, martial arts, golf, and culinary arts.

The goal is to reach youth at an early age in support of their development by fostering positive attitudes toward authority figures, while providing a safe and stable environment after school to do homework, socialize, and participate in structured summer activities. Since its inception, the program has served more than 3,000 youth.

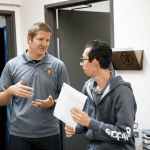

While The Salvation Army provides the facility for the program, the police department provides and pays for the personnel—including two police officers and nine college-age youth advisors. The fee for any child to become a member is $40 a year, and the balance of funding is made up through various fundraisers and in-kind donations from business owners and private citizens.

“This program is life-changing,” said Captain Terry Masango, Pasadena Tabernacle Corps Officer. “The PAL youth advisors go to the local schools and pick up the kids and bring them to our recreation center to do their homework and to learn life skills. Best of all, they get to interact with the police.”

The original PAL program, which now exists nationwide, launched in New York City in 1914 when New York City Police Lt. Ed Flynn became convinced that there was a better way to reach at-risk youth before they became involved in destructive and often harmful behavior. By rallying the neighborhood storekeepers and his fellow police officers in support of his vision, Flynn raised enough funds to buy baseball uniforms and equipment, and located a playground for games. Before the end of the year, there were nearly a dozen teams in their city, and this led to the birth of PAL.

Pasadena’s PAL program formed as part of California PAL—a group whose primary goal is to assist police and sheriff’s departments in establishing and developing PAL chapters in every community in California. This allows Pasadena’s PAL to receive supplemental funding from partner National PAL and California PAL through government grants, corporate sponsorships, and networking, sharing ideas to enhance programs.

While the PAL initiative in Pasadena is unique—no other corps in the Western Territory has one like it—similar partnerships between The Salvation Army and local police departments have cropped up in other cities, including Durham, North Carolina.

Masango noted that it’s critical for young people to have mentors, and to have positive relationships with police—especially nowadays. Tensions between police departments and communities across the country have mounted with intense media coverage and debate about the use of force in high-profile cases.

In Pasadena, serving some of the community’s most at-risk youth through PAL offers police officers a chance to build trust and bridge connections across ethnicities and ages. It’s particularly helpful for parents juggling two or three jobs, or for youth who might not have role models in their lives who are gainfully employed.

“I believe the diversity among staff helps some of the kids who may feel apprehensive about opening up, and that the kids who have gone through the program are less likely to become a statistic,” said Officer Ed Bondarczuk, who along with Officer Roxanne Haines, leads the PAL team at the Pasadena Police Department. “I tend to treat and speak to the kids as if they were my own, and I believe they appreciate that (and so do the parents).”

Jody Davis, a former police officer who serves on the board for PAL on behalf of The Salvation Army, also touted the spiritual benefits of kids interacting with corps leaders and youth ministers while participating in the program. He said various offshoots and activities include newly formed troops, similar to Girl Scouts and Boy Scouts, and field trips to museums, the beach, and other local attractions, which allow participants to try out new things, all while being well-supervised.

“We’re showing that police officers are just like everyone else,” Davis said. “They’re creating connections and friendships. They idolize them.”

Bondarczuk hopes the positive effects of PAL will permeate the whole community—even if they can’t reach all of the kids in Pasadena directly. The program is currently at capacity with 130 kids and teens, and there’s a wait list of families.

“I wish we had the capacity to take on all of the youth in Pasadena,” Bondarczuk lamented. “Gangs would be a thing of the past.”

Still, there’s reason to count what PAL has done over the past two decades as a success, not the least of which is that Haines was herself a participant in the program many years ago. The program also reports a 42 percent increase in GPA among participating kids.

“To have 130 kids spend Monday through Friday afternoons in a safe, drug-free environment is already a victory,” Masango said. “At The Salvation Army, we exist to serve those on the fringes of society, but we can’t do it alone. We’re all serving the same kids, and they’re better off in the end and better citizens through this program.”