Listen to this article

Listen to this article

Loading

Play

Pause

Options

0:00

-:--

1x

Playback Speed- 0.5

- 0.6

- 0.7

- 0.8

- 0.9

- 1

- 1.1

- 1.2

- 1.3

- 1.5

- 2

Audio Language

- English

- French

- German

- Italian

- Spanish

Open text

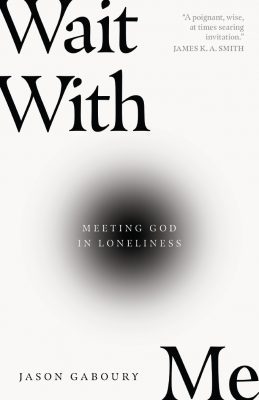

making sense of god in loneliness. by jason gaboury–. “to be human is to be lonely,” friar ugo said to me, his voice cracking with age. for 40 years he served as a jesuit missionary on the african continent. now he was sitting across from me, a thirty-something campus minister trying to make sense of god and my deep loneliness. despite the gentleness, even fragility, of his appearance, friar ugo’s words pierced the space between us like a spiritual searchlight. my heartbeat sounded in my ears, and i pressed my lips together waiting, say something else, i thought. anything. i’ve wrestled with loneliness ever since i can remember, perhaps before i can remember. growing up, my mother would tell stories about our separation at the hospital during the first six weeks of my life, or about times when, as a baby, i’d cry inconsolably for hours. exasperated, mom got in the habit of turning up the stereo and leaving me to cry it out. i don’t know what impact either of these situations had on my emerging sense of connection, but i can remember feeling lonely. that sense of loneliness dogged me through childhood, college and into adulthood. if friar ugo had observed my life from the outside, lonely would not be the adjective quick to mind. with two girls in elementary school, our home was filled with play-doh, colored paper and playdates. sophia and i parented together and partnered in ministry. our home was often full of students, friends from church, and neighbors from our building. i even had a reputation in our church for being an expert on building community. still, loneliness persisted. washing dishes late on a tuesday night after a group of friends had gone home, i’d feel strangely lonely, isolated, unknown and unloved. clearly, something wasn’t working. if anyone could help me, i thought, friar ugo could. i made an appointment to talk to him, determined to resolve this sense of isolation. for 20 minutes i’d talked about the ache of loneliness i felt even though it didn’t make sense. ugo didn’t interrupt. he sat still as the furniture, his eyes dancing with something i couldn’t place: insight, amusement, wisdom? that conversation would change my life. “loneliness is all around us,” friar ugo said. of course, i knew that. why else would i be sitting in this chair across from this old friar? you know it, too. perhaps you’ve picked up this book because you know the ache of loneliness in your situation. a friend who lived alone for many years said, “the hardest thing for me was just coming home and not having anyone to ask, ‘how was your day?’”. perhaps it seems as if all the friends you used to talk with into the early morning hours have moved away or gotten married. perhaps you’re a young parent caught in the valley of diapers, isolated from other adults and emotionally exhausted. perhaps you’re in a new job or school and miss the familiar faces and relationships. the technological solution to our loneliness seems to be in our grasp. social media platforms like facebook, twitter and instagram are changing the way we see ourselves and the way we have relationships. we can create online communities or chat groups and instantly communicate with people across the world. with access to so many human connections you’d think loneliness would be a thing of the past. we’ve never been lonelier. katherine hobson, citing a study released in 2017, reports:. it turns out that the people who reported spending the most time on social media—more than two hours a day—had twice the odds of perceived social isolation than those who said they spent a half hour per day or less on those sites. and people who visited social media platforms most frequently, 58 visits per week or more, had more than three times the odds of perceived social isolation than those who visited fewer than nine times per week. a friend said recently, “we can have a thousand friends on facebook, but based on how we spend our time, it seems like facebook is worth a thousand friends.”. it’s wrong though to place the blame for our social dislocation squarely on the shoulders of social media. robert putnam’s famous book “bowling alone” describes the fragmentation and isolation of american community before the rise of social media. he says, “americans are right that the bonds of our communities have withered and we are right to fear that this transformation has very real costs.”. increasing loneliness, according to putnam, has to do with the decrease in neighborhood societies, civic organizations, religious communities and social clubs. loneliness is not just a modern problem. it’s an ancient problem because it’s a human problem. ultimately, loneliness is a spiritual problem. loneliness is no joke. isolation is so powerfully disorienting that solitary confinement is classified as a form of torture. as i sat in that chair across from friar ugo, i could feel the primordial weight of loneliness pressing in on me. i knew the story of genesis 2. not good that the man should be alone. so i thought, god, fix it! i wanted friar ugo to tell me how god was going to take the isolation away. instead, he started talking about something else. “have you ever considered,” he asked, “that the loneliness you’re experiencing is an invitation to grow your friendship with god?”. i hadn’t. friar ugo went on, “loneliness is part of the human condition. it is the experience of many around the corner who are living on the street. it is the experience of many around the world, separated from home, family and land because of war or disease. and,” he paused, “it was often the experience of our lord himself. you can look to me…or to something else…even to religion to try to make you feel better. or,” he said, clearing his throat, “you could see this as the beginning of god’s work of transformation in you.”. and then we sat there in silence. i pressed my lips together again, but something in his invitation had already stirred inside me. what if loneliness was a doorway to a deeper life with god? what would that mean? how might this idea reshape the experience? after a short prayer our conversation ended. friar ugo didn’t share stories of his isolation in ministry. he didn’t talk, for example, about being forced to leave a country and a context he loved and not being allowed to return despite years of continued effort. he didn’t describe his experience of returning to new york after forty years on the mission field. he simply prayed, and then i stepped out into the cold new york city morning with lots of questions. what would it look like to respond to god’s invitation in the midst of loneliness? was this a biblical idea? if so, what might scripture have to teach about loneliness as a place of transformation? to my surprise, the old and new testaments are full of examples of women and men who met god in the midst of loneliness or isolation. abraham experienced loneliness in his desire for family: “oh that ishmael might live in your sight!” (genesis 17:18). moses experienced loneliness when he fled egypt. jacob experienced loneliness in the face of his ambition. elijah faced loneliness in fatigue after his great victory. nehemiah faced loneliness in leadership as he dealt with opposition from outside and sabotage within. job experienced loneliness in suffering while his friends offered little comfort. esther experienced loneliness in the palace: “but as for me, i have not been called to come in to the king these thirty days” (esther 4:11 esv). mary chose loneliness in her embrace of god’s call: “behold, i am the servant of the lord; let it be to me according to your word” (luke 1:38 esv). paul experienced loneliness in mission. ultimately jesus experienced the deepest loneliness of all as he cried out, “my god, my god, why have you forsaken me?” (matthew 27:46). these stories reveal god’s transforming presence and power in the lives of individuals and communities. they meet god in the midst of loneliness and are changed. some walk away with a limp. some walk away with deepened courage. the thought struck me, what might i walk away with if i immersed myself in their stories? turns out, we can learn a lot by sitting in the ashes with job or in the wilderness with hagar. god invites us into these stories, saying, “wait with me.” entering these stories reframes our understanding of loneliness by demonstrating god’s presence and purpose. it enlarges our heart to connect with the isolation of our spiritual forebears and perhaps to connect more deeply with others who face similar loneliness and isolation. through these stories we are taught to hope in god’s future. taken from wait with me by jason gaboury. copyright (c) 2020 by jason gaboury. published by intervarsity press, downers grove, il. do good:. read “wait with me” by jason gaboury (intervarsity press, 2020). choose one of the old and new testaments examples of women and men who met god in the midst of loneliness or isolation mentioned here. read their story and look for the lessons in their loneliness. see how you can get involved in the fight for good at westernusa.salvationarmy.org. do you have a hard time telling people what you do, or what you’re passionate about and why? ever stared at a blinking cursor, unsure of what to say or where to start? or do you avoid writing altogether because you’re “not creative enough”? take our free email course and find your story today.

Open context player

Close context player

Plays:-Audio plays count

making sense of god in loneliness. by jason gaboury–. “to be human is to be lonely,” friar ugo said to me, his voice cracking with age. for 40 years he served as a jesuit missionary on the african continent. now he was sitting across from me, a thirty-something campus minister trying to make sense of god and my deep loneliness. despite the gentleness, even fragility, of his appearance, friar ugo’s words pierced the space between us like a spiritual searchlight. my heartbeat sounded in my ears, and i pressed my lips together waiting, say something else, i thought. anything. i’ve wrestled with loneliness ever since i can remember, perhaps before i can remember. growing up, my mother would tell stories about our separation at the hospital during the first six weeks of my life, or about times when, as a baby, i’d cry inconsolably for hours. exasperated, mom got in the habit of turning up the stereo and leaving me to cry it out. i don’t know what impact either of these situations had on my emerging sense of connection, but i can remember feeling lonely. that sense of loneliness dogged me through childhood, college and into adulthood. if friar ugo had observed my life from the outside, lonely would not be the adjective quick to mind. with two girls in elementary school, our home was filled with play-doh, colored paper and playdates. sophia and i parented together and partnered in ministry. our home was often full of students, friends from church, and neighbors from our building. i even had a reputation in our church for being an expert on building community. still, loneliness persisted. washing dishes late on a tuesday night after a group of friends had gone home, i’d feel strangely lonely, isolated, unknown and unloved. clearly, something wasn’t working. if anyone could help me, i thought, friar ugo could. i made an appointment to talk to him, determined to resolve this sense of isolation. for 20 minutes i’d talked about the ache of loneliness i felt even though it didn’t make sense. ugo didn’t interrupt. he sat still as the furniture, his eyes dancing with something i couldn’t place: insight, amusement, wisdom? that conversation would change my life. “loneliness is all around us,” friar ugo said. of course, i knew that. why else would i be sitting in this chair across from this old friar? you know it, too. perhaps you’ve picked up this book because you know the ache of loneliness in your situation. a friend who lived alone for many years said, “the hardest thing for me was just coming home and not having anyone to ask, ‘how was your day?’”. perhaps it seems as if all the friends you used to talk with into the early morning hours have moved away or gotten married. perhaps you’re a young parent caught in the valley of diapers, isolated from other adults and emotionally exhausted. perhaps you’re in a new job or school and miss the familiar faces and relationships. the technological solution to our loneliness seems to be in our grasp. social media platforms like facebook, twitter and instagram are changing the way we see ourselves and the way we have relationships. we can create online communities or chat groups and instantly communicate with people across the world. with access to so many human connections you’d think loneliness would be a thing of the past. we’ve never been lonelier. katherine hobson, citing a study released in 2017, reports:. it turns out that the people who reported spending the most time on social media—more than two hours a day—had twice the odds of perceived social isolation than those who said they spent a half hour per day or less on those sites. and people who visited social media platforms most frequently, 58 visits per week or more, had more than three times the odds of perceived social isolation than those who visited fewer than nine times per week. a friend said recently, “we can have a thousand friends on facebook, but based on how we spend our time, it seems like facebook is worth a thousand friends.”. it’s wrong though to place the blame for our social dislocation squarely on the shoulders of social media. robert putnam’s famous book “bowling alone” describes the fragmentation and isolation of american community before the rise of social media. he says, “americans are right that the bonds of our communities have withered and we are right to fear that this transformation has very real costs.”. increasing loneliness, according to putnam, has to do with the decrease in neighborhood societies, civic organizations, religious communities and social clubs. loneliness is not just a modern problem. it’s an ancient problem because it’s a human problem. ultimately, loneliness is a spiritual problem. loneliness is no joke. isolation is so powerfully disorienting that solitary confinement is classified as a form of torture. as i sat in that chair across from friar ugo, i could feel the primordial weight of loneliness pressing in on me. i knew the story of genesis 2. not good that the man should be alone. so i thought, god, fix it! i wanted friar ugo to tell me how god was going to take the isolation away. instead, he started talking about something else. “have you ever considered,” he asked, “that the loneliness you’re experiencing is an invitation to grow your friendship with god?”. i hadn’t. friar ugo went on, “loneliness is part of the human condition. it is the experience of many around the corner who are living on the street. it is the experience of many around the world, separated from home, family and land because of war or disease. and,” he paused, “it was often the experience of our lord himself. you can look to me…or to something else…even to religion to try to make you feel better. or,” he said, clearing his throat, “you could see this as the beginning of god’s work of transformation in you.”. and then we sat there in silence. i pressed my lips together again, but something in his invitation had already stirred inside me. what if loneliness was a doorway to a deeper life with god? what would that mean? how might this idea reshape the experience? after a short prayer our conversation ended. friar ugo didn’t share stories of his isolation in ministry. he didn’t talk, for example, about being forced to leave a country and a context he loved and not being allowed to return despite years of continued effort. he didn’t describe his experience of returning to new york after forty years on the mission field. he simply prayed, and then i stepped out into the cold new york city morning with lots of questions. what would it look like to respond to god’s invitation in the midst of loneliness? was this a biblical idea? if so, what might scripture have to teach about loneliness as a place of transformation? to my surprise, the old and new testaments are full of examples of women and men who met god in the midst of loneliness or isolation. abraham experienced loneliness in his desire for family: “oh that ishmael might live in your sight!” (genesis 17:18). moses experienced loneliness when he fled egypt. jacob experienced loneliness in the face of his ambition. elijah faced loneliness in fatigue after his great victory. nehemiah faced loneliness in leadership as he dealt with opposition from outside and sabotage within. job experienced loneliness in suffering while his friends offered little comfort. esther experienced loneliness in the palace: “but as for me, i have not been called to come in to the king these thirty days” (esther 4:11 esv). mary chose loneliness in her embrace of god’s call: “behold, i am the servant of the lord; let it be to me according to your word” (luke 1:38 esv). paul experienced loneliness in mission. ultimately jesus experienced the deepest loneliness of all as he cried out, “my god, my god, why have you forsaken me?” (matthew 27:46). these stories reveal god’s transforming presence and power in the lives of individuals and communities. they meet god in the midst of loneliness and are changed. some walk away with a limp. some walk away with deepened courage. the thought struck me, what might i walk away with if i immersed myself in their stories? turns out, we can learn a lot by sitting in the ashes with job or in the wilderness with hagar. god invites us into these stories, saying, “wait with me.” entering these stories reframes our understanding of loneliness by demonstrating god’s presence and purpose. it enlarges our heart to connect with the isolation of our spiritual forebears and perhaps to connect more deeply with others who face similar loneliness and isolation. through these stories we are taught to hope in god’s future. taken from wait with me by jason gaboury. copyright (c) 2020 by jason gaboury. published by intervarsity press, downers grove, il. do good:. read “wait with me” by jason gaboury (intervarsity press, 2020). choose one of the old and new testaments examples of women and men who met god in the midst of loneliness or isolation mentioned here. read their story and look for the lessons in their loneliness. see how you can get involved in the fight for good at westernusa.salvationarmy.org. do you have a hard time telling people what you do, or what you’re passionate about and why? ever stared at a blinking cursor, unsure of what to say or where to start? or do you avoid writing altogether because you’re “not creative enough”? take our free email course and find your story today.

Listen to this article